About Injectable Antibiotics

Globally, neonatal sepsis accounts for over 500,000 newborn deaths annually[1]. Newborn infection has a rapid onset, and urgent diagnosis and presumptive treatment is needed[2].

Commodity Introduction

Neonatal sepsis is a blood infection that occurs in an infant younger than 90 days old. Early-onset sepsis is seen in the first week of life and late-onset sepsis occurs between days 8 and 89. The risk of death is great for newborns with serious infections, whether hospitalized or in the community, with mortality rates of early-onset sepsis (7 days) between 2% and 20%[3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that antibiotic treatment with benzylpenicillin and gentamicin be used as first-line therapy for presumptive treatment in newborns at risk of bacterial infection and ceftriaxone delivered alone for the treatment of neonatal sepsis as a second-line therapy[4].

Commodity Context

Since newborn infection has a rapid onset, urgent diagnosis and presumptive treatment are needed. However, sick newborns often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms, making diagnosis of neonatal sepsis particularly difficult in many low-resource settings. Deaths are often due to delays in the identification and treatment of newborns with infection, specifically, under-recognition of illness, lack of access to appropriate treatment and trained health workers to administer it, delay in initiation of treatment, and inability to pay for treatment by families, if warranted. Studies suggest that the currently recommended antibiotics are not readily available or are subject to stock-outs in weaker health systems and particularly in remote areas.

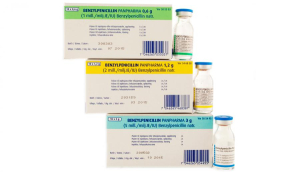

Products Available

Injectable procaine benzylpenicillin, gentamicin, and ceftriaxone are available throughout the world. Over 50 different countries throughout Asia and South Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America manufacture these drugs, with the majority of manufacturers located in China, India, and the United States. However, in both Asia and sub-Saharan Africa formulations at appropriate dosage for newborns may not be readily available from manufacturers.

Product Efficacy

A review of available data about injectable antibiotics for treatment of neonatal infections in developing-countries found that penicillin and cephalosporins have relatively favorable efficacy and safety profiles.[5] Gentamicin also appears to be safe and effective when used appropriately, despite its narrow therapeutic indices. Although inexpensive and effective, chloramphenicol is the least preferred due to its potential association with significant life-threatening toxicity among neonates. Overall, the WHO recommended first-line and second-line treatments are safe and retain efficacy when injected properly at extended intervals (24 hours).

Common Barriers

There are a number of social and behavioral barriers that hinder the uptake of this commodity by skilled providers. Sick newborns often present with non-specific signs and symptoms, making the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis difficult in low-resource settings and as a result, treatment--if sought at all--is often received too late.

Community-level barriers can also limit the use of injectable antibiotics to treat neonatal sepsis. In some countries, low demand for neonatal health care limits the use of health services. Additionally, limited access to media, a few irrelevant or inappropriate messages, the use of traditional practices and fatalistic beliefs also contribute to lack of demand for neonatal care. The lack of pediatric syringes and difficulty of filling other syringes with the small dose needed also generate further challenges for injectable antibiotics provision at the community level.

At the policy level, not all countries include the antibiotics used to treat neonatal sepsis in their national policies--including their essential medicines lists--and little is known about the availability and use of these drugs at various levels of national health systems. National strategies need to address community-based treatment and management of neonatal sepsis by lay health workers. However, current research indicates that there is no clear agreement by policymakers on the optimal antibiotic treatment in the community.

For more information on injectable antibiotics, please visit the UN Every Woman Every Child Initiative webpage.

[1] Robert E. Black, Simon Cousens, Hope L. Johnson, Joy E. Lawn, Igor Rudan, Diego G. Bassani . . . Richard Cibulskis. (2010). Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 375(9730), 1969-1987.

[2] Mikkel Zahle Oestergaard, Mie Inoue, Sachiyo Yoshida, Wahyu Retno Mahanani, Fiona M. Gore, Simon Cousens . . . Colin Douglas Mathers. (2011). Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS medicine, 8(8), e1001080.

[3] Neonatal sepsis web page (2012), from http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/infections_in_neonates/neonatal_sepsis.html#v1092175

[4] World Health Organization (2013). WHO model list of essential medicines for children: 4h list (updated) April 2013.

[5] Gary L. Darmstadt, Maneesh Batra & Anita K. M. Zaidi. (2009). Parenteral antibiotics for the treatment of serious neonatal bacterial infections in developing country settings. The Pediatric infectious disease journal, 28(1), S37-S42.

This website is made possible by the support of the American People through the

This website is made possible by the support of the American People through the