Provider Motivations

Worker motivation is critically important in the health sector. Evidence has shown that motivated workers come to work more regularly, work more diligently, and are more flexible and willing and reflect better attitudes towards the people they serve. (HWM, Hornby and Sidney 1988).

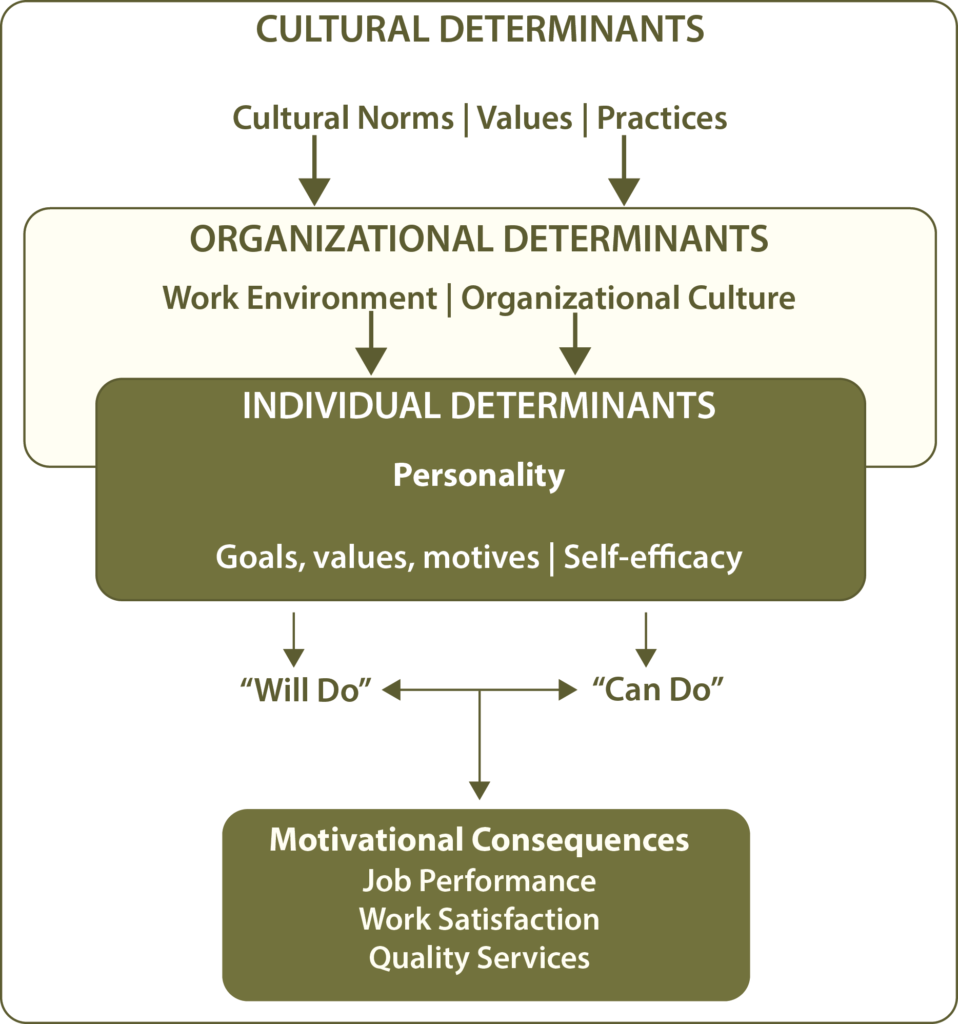

Motivation is a complex process. A provider’s motivation to deliver high-quality services is impacted by the interaction of many factors at the Individual, Organizational, and Cultural levels (Mathauer and Imhoff, 2006 http://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-4-24). SBCC interventions need to address determinants across these categories to improve motivation and service provision. The graphic below shows how these factors interact to develop motivation.

Adapted from Mathauer and Imhoff, 2006.

Attitudes, beliefs, values, and norms play an important role in provider motivation and, consequently, on their patient’s health care experience. In addition to having an impact on their interaction with their patients, providers’ attitudes and beliefs can also influence their motivation to make changes to their own practices and behaviors, how they perform their jobs, and their desire to continue as a member of the health care workforce altogether.

Different cadres of health workers possess different motivations. To design an effective SBCC intervention, it is critical to understand those motivations. This section of the I-Kit will provide background research on the most common motivational factors for Community Health Workers and Facility-Based Providers. In the Design section, you will have the chance to identify which of these specific motivators are relevant to your intended audience.

While factors from the Expectation, Opportunity, and Ability categories can impact Motivation, this I-Kit focuses mainly on the internal motivating factors influencing provider behavior. See the Resources section for examples of interventions that have addressed Expectation, Opportunity, and Ability factors.

Motivating CHWs in Tanzania

A study of CHW motivating factors in Tanzania determined that motivating factors for CHWs often differed across socio-demographic characteristics. For example, older and less educated CHWs were more likely to be motivated by altruism, intrinsic needs, community respect and getting new skills. Wealthier CHWs indicated quality job aides were important to job satisfaction and motivation.

Mpembeni, R. N., Bhatnagar, A., LeFevre, A., Chitama, D., Urassa, D. P., Kilewo, C., … & George, A. (2015).Motivation and satisfaction among community health workers in Morogoro Region, Tanzania: nuanced needs and varied ambitions.Human resources for health, 13(1), 44.

Community Health Worker Motivations

Factors impacting CHW motivation and desire to perform well can be grouped into five categories:

- Perceived status and social support: The extent to which a CHW feels recognized or appreciated by their respective community, peers, facility- based providers and/or the larger health system.

- Level of connectedness: Feeling connected to one’s CHW peers, supervisor, community and formal health system.

- Incentives and personal rewards: The feeling that one or more of an individual’s personal needs are met. These vary by CHW but typically include: feeling of social responsibility, desire for achievement, opportunities for personal growth and career development, financial and non-financial incentives.

- Supportive social and gender norms: The extent of feeling enabled or restricted by prevailing social and gender norms in both the organizational system or community at large.

- Personal attitudes and beliefs: Provider values, attitudes and beliefs, as well as individual personality traits.

Perceived Status and Social Support

Perceived social status and support is critical to improving CHW performance and is closely tied to CHW retention. Because CHWs are either volunteer or minimally paid, and have the lowest levels of education and economic status, they are often looked down upon by some members of the community and by trained health providers. In comparison to other health workers, CHWs are often considered the lowest status within the health system. (Said, et al. 2014)

Negative attitudes on the part of community members and health providers toward CHWs can result in conflicts with health providers, long wait times at clinics or rejection of referrals made by CHWs. Sometimes community members do not trust what the CHW says because the CHW is not a doctor and is often “just somebody’s neighbor.” Ministries of Health often do not treat them as a formal cadre of health worker in order to ensure the CHWs stay “of the community.” As a result, CHWs’ sense of inclusion in, and support from, the health system is diminished.

Furthermore, lack of family support, including unwillingness to take on CHW household tasks neglected due to CHW responsibilities, and open or implied discouragement from peers or family members, have also been documented as limiting CHW motivation.

In some cases, becoming a CHW can elevate social status, thus creating a barrier between the CHW and the client. CHWs sometimes adopt an attitude that they are “better” than their clients because they received education or were chosen by community members.

Level of Connectedness

The extent to which a CHW feels connected to their community, the health system, to their peers and to their supervisors is critical to CHW motivation, retention and effectiveness.

- Community Connectedness– The extent to which a CHW feels rooted in the local community and tied to the community goals and objectives is a key factor to CHW motivation. One of a CHW’s primary duties is to tailor health promotion and service delivery strategies in a way that reflects the norms and cultural dynamics of the community. This requires that the CHW is known and trusted by the community.

- Peer Connectedness– Interaction with other CHWs can be a critical motivator for people who often work with little supervision or tangible evidence of their effectiveness. Many volunteers work independently and may not have an opportunity to interact with their peers, leaving them to feel alone and lacking support.

- Connectedness to Supervisor– While the level and type of interaction with a supervisor is impacted by cultural norms and values, feelings of connectedness to supervisors and management, it is often identified as key to CHW motivation. Additionally, weak, inadequate (punitive instead of coaching) and inconsistent supervision is frequently cited as a cause of low CHW motivation, morale and high attrition.

- Connectedness to Health Facilities– CHWs play an important role in creating demand for and making referrals to services provided in health facilities. It is critical that CHWs are well connected to and supported by the broader health system. For example, CHWs need a clear job description with defined tasks and a system for incentives and/or payment. Additionally, CHWs should receive training, materials, and routine support from the health system. The absence of these things is directly tied to low CHW job satisfaction, lack of status, and feelings of exclusion.

Incentives and Personal Rewards

A considerable focus has been placed on material or ‘direct’ incentives and to some extent indirect or non-material incentives as a means of motivating CHWs. Recognizing that most CHWs represent poor communities and are themselves often lower income, offering CHWs some form of financial incentive can positively impact motivation. However this is often not enough as not all CHWs find sufficient personal reward in material compensation. There should also be caution in using financial rewards since those extrinsic motivators can crowd out intrinsic motivators.

Usually, CHWs are motivated by a mix of financial and non-financial rewards. The types of rewards and incentives that motivate providers are influenced both by individual needs and desires, local socio-economic context, and cultural and social norms. Some examples include:

- A feeling of social responsibility, a desire to help others and make a difference

- Desire for achievement and advancement

- Opportunities for growth, including learning or training opportunities and exposure to new situations

- Recognition or appreciation for the work they have done – from community members, peers, and supervisors

- Non-financial incentives, including use of a tablet or phone, special work attire, or education opportunities for family members

- Financial incentives, including salaries and bonuses

Social and Gender Norms

Community health workers both represent and are influenced by the social context in which they live and work. Prevailing social norms impact the beliefs, values and attitudes of both CHWs and their clients. Broad cultural values and social norms can translate into specific types of work behaviors, including the way in which providers interact with community members and clients and vice versa. For example, in many countries individuals are more likely to believe that fate is outside of one’s control. This may impact a client’s willingness to listen to or accept information from a CHW, leading the CHW to potentially feel ineffective and not valued. In many places cultural beliefs forbid sex before marriage, and as a result CHWs may believe that adolescents should not use contraceptives and refuse to counsel or provide them contraceptives.

Prevailing norms about what is considered “women’s work,” and whether women are allowed to work outside of the home may influence the number of women referred as CHWs, the amount of time they can commit to the work and/or the level of support they receive from partners to take on household chores when they do become busy with CHW. In northeastern Bangladesh, for example, female CHWs cited family expectations including prioritizing marriage, stigma towards female CHWs or social norms that limit women’s work at night or outside of the home as reasons for drop out. In Uganda, some male CHWs feel pressure from families because their volunteer work limits their ability to meet expectations to be a material provider. In Lesotho as in many countries, CHW work is generally considered “female work” and men rarely apply.

The table below summarizes how three key dimensions of culture: conservatism, level of hierarchy, and mastery versus harmony may also impact CHW motivation, attitudes and performance and interactions between clients and CHWs. It is important to understand which if any of these are relevant in your local context as you adapt or design programs to address social and cultural norms.

| DIMENSIONS | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Conservatism vs. autonomy: the relationship between the individual and group | The degree to which individuals are embedded in the collectivity, find meaning largely through social relationships, or whether individuals find meaning in their own uniqueness and individual action. |

| Hierarchy vs. egalitarianism: assuring responsible social behavior | The degree to which individuals are socialized and sanctioned to comply with obligations and rules attached to their roles, as ascribed by a hierarchical system. Or a more egalitarian view, where individuals are portrayed as moral equals and people are socialized to internalize a commitment to voluntary cooperation and concern for others. |

| Mastery vs. harmony: the role of humankind in the natural and social world | The degree to which people see their roles as one of submitting, fitting in or exploiting the natural social world in which they live. |

Source: Schwartz, “Values and Culture.”

Personal Attitudes and Beliefs

A CHW’s personal attitudes, values, and beliefs are strongly influenced by wider social norms. However, each CHW’s attitudes and beliefs will be different due to participation in different social groups; family dynamics; and individual personality traits.

These personal attitudes and beliefs can influence a CHW’s willingness to interact with a client or provide certain services as well as the way they treat the client. They can result in stigmatizing or aloof behavior. Some of the most relevant attitudes and beliefs include:

- Attitudes toward their work, positions and responsibilities

- Attitudes toward co-workers and superiors

- Attitudes/beliefs about the health topic, particularly if it is controversial, taboo, or difficult to discuss

- Attitude toward the client, influenced by the client’s socioeconomic status, current behaviors, occupation, ethnicity, religion, or language

- Beliefs about the products and services they offer and who should be able to access them

- Beliefs about the health behavior, what should and should not be done, and acceptability of use

Facility-Based Provider Motivations

Factors impacting FBP motivation and desire to perform well can be grouped into five categories:

- Self-efficacy: The extent to which providers believe their efforts will be successful.

- Social and gender norms: The extent of feeling enabled or restricted by prevailing social and gender norms in both the organizational system or community at large.

- Perceived place in social hierarchy/status: Where the providers feel they fit in the larger social structure, or perceived status relative to the clients and community members.

- Rewards: The extent to which the providers feel personally fulfilled by their work and sense that others care about what they are doing.

- Work environment: The extent to which providers have a supportive work environment and the health team has norms for providing quality services.

Self-Efficacy

Even when providers are adequately trained and possess the knowledge and skills to do their jobs, they still may feel unmotivated. A key determinant to motivation is providers’ belief in their ability to succeed. They must believe that what they are doing will be effective and that they have the ability to complete the task. If providers believe they are unlikely to succeed, they are usually not motivated to begin or continue a particular task or behavior.

Feelings of self-efficacy have a significant effect on the level of motivation and amount of extended effort a provider demonstrates. High levels of self-efficacy are associated with an increased level of goal setting, which leads to a firmer commitment in achieving goals that have been set and greater resolve to persevere in the face of obstacles.

In the health center context, three factors influence provider self-efficacy: environment, degree of autonomy, and self-perception.

- Environment: A provider’s learning and working environment shape feelings of self-efficacy. Within the health center, there must be resources, supportive procedures, and team support to help providers feel confident that they will be able to diagnose, counsel, and treat effectively. For example, verbal praise or recognition from a supervisor and low levels of conflict can help increase feelings of self-efficacy while a heavy workload, lack of job clarity, and poor cooperation among team members can limit feelings of self-efficacy. Within the community, providers need to feel able to treat without fear of reprisal and feel confident that their counsel will be followed to ensure treatment efficacy. For example, if a nurse sees that her clients repeatedly discontinue their course of antibiotics, she will feel less effective with her clients and less able to have a positive impact.

- Degree of autonomy: To feel confident in their ability to succeed, providers need to have the flexibility to problem-solve and a sense that they have some control over the situation. Being able to use individual discretion and critical thinking skills increases feelings of self-efficacy because they provide a sense of ownership and self-determination over the tasks at hand. If providers believe that external forces determine success, they are unlikely to believe that what they do will make a difference. Even when a goal should be easy to achieve, if providers sense that they do not have control over a situation, self-efficacy decreases. For example, if a nurse is bound by strict regulations and is told that he can only take orders from the doctor, he will be less creative in addressing problems as they arise. He will feel that his actions will not change the outcome and will feel ineffective with his clients.

- Self-perception: Providers beliefs about their own attributes influence how successful they will be with a given task. A provider’s belief about how strong or capable she is, or what kind of person she is can facilitate or prevent behaviors. For example, if a doctor thinks she just isn’t the empathic type or believes that she isn’t assertive enough to get the support she needs, she will be less successful with those behaviors.

Social and Gender Norms

Facility-based providers both represent and are influenced by the social context in which they live and work. Prevailing social norms impact the beliefs, values and attitudes of both the providers and their clients. Broad cultural values and social norms can translate into specific types of work behaviors, including the way in which providers interact with community members and clients and vice versa. The attitudes providers adopt due to the larger social norms can impact both the what and the how of service provision.

What: Providers may not be willing to provide certain services or products to certain populations. For example, a cultural norm that a newlywed couple needs to prove fertility and have a child soon after marriage can influence a provider’s willingness to offer contraceptives to the couple. Or, a provider may refuse service to men who have sex with men because society believes that homosexuality is immoral.

How: Providers often offer lower quality services to certain populations due to cultural beliefs and norms. For example, providers may make public announcements in the waiting room that all sex workers present should line up at the back or stand in a separate line because their occupation is socially unacceptable. Or, providers may spend less time with socially stigmatized populations or not respect their confidentiality.

Gender norms may also impact how a provider interacts with a client. Some topics may be taboo or providers and clients might feel uncomfortable asking relevant questions. A provider’s sex can even influence the type and topic of training received, making it difficult for some providers to effectively counsel or treat.

Perceived Place in Social Hierarchy

Due to their education level and the respect accorded their position, providers often enjoy a higher status in the larger social hierarchy than many of their clients. This elevated status may motivate providers, given that they feel recognized and valued for their contribution to society. Their elevated status may also contribute to client trust and compliance. However, a provider’s perceived status can also be a barrier to quality service provision.

Providers’ perceptions about their own status can influence their personal values and beliefs, particularly about their clients. Providers often spend years on their education, between their initial training and continuing education. Frequently, this training encourages providers to be different from their communities, creating a culture of social distance between provider and client. This can contribute to disrespectful attitudes where providers believe that they know better and that they do not need to listen to their clients. Providers often have a higher socioeconomic status, which places them on a different level than many of their clients. Their advanced education, socioeconomic status, and experience can lead providers to believe they have earned the right to treat clients poorly, particularly in a class conscious society. Providers’ relationships with clients are frequently framed through a culture of paternalism that assumes clients – especially if less educated, younger, or female, have limited awareness or agency in health-related decision-making. This power imbalance between providers and clients can lead to poor treatment and health outcomes. For example, doctors or nurses might yell at clients, scold, humiliate, or discount their pain. Some laboring women report being hit, shouted at, and threatened by nurses and doctors.

Clients’ past experience with poor treatment, humiliation, or being refused treatment due to this power imbalance also impacts the way they interact with providers. Some clients may decide not to come to the health facility at all. Judgmental and rude treatment have been found to be major barriers to seeking care. Others may come but choose not to share certain information or ask important questions that could impact a diagnosis or treatment decision. Thus, status and hierarchy issues need to be addressed at both the provider and the client level.

Personal Rewards

Provider motivation increases when their own needs are met and when they feel that others care about the good work they are doing. Motivation is likely to suffer when workers think that nobody will notice their hard efforts or when they see workers whose productivity is low receiving rewards equal to those who try harder. These rewards can be intrinsic or extrinsic.

Intrinsic

- Perceived importance of work: When providers perceive that what they are doing has great value, they are more willing to try new behaviors or strategies to improve client outcomes. They are also more able and willing to endure hardships, including low pay and lack of resources. When providers are able to see that what they are doing improves or saves lives, motivation often increases. The perceived sense of importance impacts providers’ attitudes toward their work and their clients.

- Learning opportunities and personal development: Provider motivation, performance, and job satisfaction are all strongly linked to opportunities for training and learning new skills. Providers value continuing education as a chance to expand their understanding, enhance effectiveness, and increase likelihood of advancement. These learning opportunities allow providers to assume more demanding duties and make advancement more likely. The skills learned can also help providers problem solve and cope with their jobs.

- Appreciation and recognition: A major motivator for providers (often right behind pay) is appreciation or recognition. This appreciation can come from supervisors/management, colleagues/peers, and clients. Providers need to hear specifically how they are appreciated and feel supported to achieve goals. They want to see that they are being useful to society and know that the community trusts and values them. Appreciation can be as simple as praise for a job well done or recognition of the difficulties endured. Or, it can be a more involved recognition campaign where providers are recognized publically for their contributions or where health centers are awarded for reaching quality standards.

Extrinsic

- Financial gains: Financial compensation – in the form of salary, bonuses, or other financial rewards – is often one of the more important motivating factors. However, financial rewards are rarely sufficient to motivate providers. There should also be caution in using financial rewards since those extrinsic motivators can crowd out intrinsic motivators. Usually, a mix of financial and non-financial rewards works best to motivate providers.

- Other incentives: Other non-monetary incentives can also motivate providers. Improved clinic environment, opportunities to use annual leave, and improved working conditions – including addressing high workloads – can improve motivation. Providers are also often interested in better staff accommodations, good schools and teachers for their children, and health care benefits.

- Career advancement: Providers are also motivated by chances for career advancement. This can include opportunities for specialization through further training, or merit-based promotion. When there are opportunities for specialization and promotion, providers believe that their good work is noticed and appreciated, and that they have an adequate amount of challenge in their work. Providers have a sense of pride when they perceive there are opportunities to progress.

Work Environment

A provider’s work environment is foundational to being able to provide quality services. Providers’ relationships with colleagues, the type and quality of supervision, and the group norms within the health center all impact motivation.

The relationships a provider has with colleagues play a major role in the provider’s attitude toward work and levels of motivation. High levels of conflict, rivalries between cadres, a competitive environment, and lack of appreciation contribute to dissatisfaction and low desire to be at work. On the other hand, relationships characterized by high levels of trust, mutual respect, and appreciation lead to increased motivation and performance.

The type and quality of supervision, as well as the kind of relationship providers have with management, are critical determinants of motivation. Often supervision visits focus on record-keeping, attendance, and fault-finding. Supervisory practices that are consistent, relevant, and positive are linked to improved motivation and performance. Providers need to have regular interaction with their supervisors, and the interaction needs to go beyond corrective action. Motivation can be improved through enhancements to supervisory practices, including continuous supervision occurring in a variety of contexts rather than only periodic visits by external supervisors, provision of on-site technical support and training and joint problem solving, and regular follow-up. Supportive supervision where providers receive positive feedback, reinforcement, and support for problem solving is important to maintaining motivation.

Supervisors also need adequate management and leadership skills that enable them to motivate their providers. In many settings, due to insufficient resources, supervisors are not trained and are not equipped to lobby on behalf of their providers. Without those skills and commitment, providers suffer and motivation decreases.

Group norms and teamwork are another key component of provider motivation. All the employees in the health center make up a team. Every team creates group norms, some explicit and others implicit. These norms govern how the team works together. Successful teams are characterized by two norms: equal participation, and social sensitivity. In the health center, norms about including all employees in health facility management meetings, allowing all to speak roughly the same amount, and offering opportunities to participate in decision-making processes, can provide a sense of ownership and develop motivation. Norms around seeking to understand how others feel and being sensitive to those feelings creates a safe space filled with trust and respect. People on the team are comfortable saying what they think and being themselves. These two norms create a positive working environment where employees work together.

It is also important to foster positive norms around how employees treat clients and a common vision for quality service provision. Typically, those norms flow from the equal participation and social sensitivity norms that begin to impact personal values and beliefs about others. When there are positive group norms and teamwork, providers feel more motivated and the health center is more effective at reaching its goals.