ABOUT THIS I-KIT

This Implementation Kit (I-Kit) was developed to help social and behavior change communication (SBCC) and malaria in pregnancy (MiP) program managers and stakeholders address identified gaps and improve SBCC strategies and interventions for MiP, especially those interventions that target healthcare workers. This guidance is divided into four sections:

Background

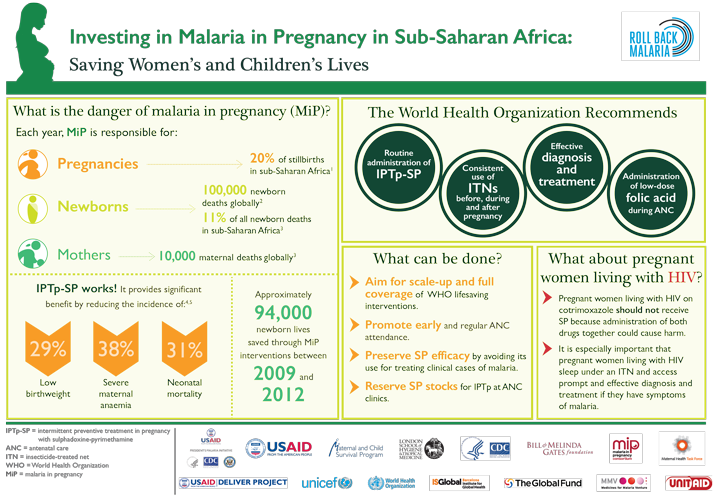

The Roll Back Malaria MiP Working Group produced a two-page infographic to raise awareness and advocate for increased resources to prevent MiP.

MiP is a significant public health issue with harmful consequences for not only pregnant women, but also for unborn and newborn children.1 Every year, MiP is responsible for the death of over 100,000 newborns and 10,000 pregnant women around the world.2 MiP is also associated with anemia, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight and severe malaria. Young women in their first and second pregnancies and those who are infected with HIV are at highest risk.3 MiP-associated illnesses are most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa.

Given MiP’s prevalence and severity, it is crucial that malaria prevention and control interventions effectively reach and support women before and during pregnancy. Fortunately, the means to prevent and treat MiP are inexpensive and cost-effective. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the following evidence-based strategies to prevent, diagnose and treat MiP4:

- Use of long lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) by pregnant women

- Scale-up of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in all areas in sub-Saharan Africa with moderate to high malaria transmission

- Prompt diagnostic testing of suspected malaria and treatment of confirmed malaria infections

ANC 4

ITN Use

IPTp 3+

This advocacy guide is designed to help countries put an advocacy plan in place to scale up MiP interventions nationwide. It includes an MiP scorecard to measure achievements over time.

Through the scale up of effective interventions, the global malaria incidence was reduced by 37 percent and global malaria mortality by 60 percent between 2000 and 2015.5 Between 2009 and 2012 alone, 94,000 newborn lives were saved through MiP interventions.6 Despite these gains, scale up of interventions to prevent and treat MiP remain suboptimal.7 In 2014, 40% or pregnant women received two or more doses of IPTP and only 17 percent received the recommended three or more doses.8 Data from ten sub-Saharan African countries taken between 2009 and 2013 also found that just 35 percent of pregnant women in households with at least one ITN used one.9 At the community level this is, in part, a result of low access to and demand for interventions to prevent and treat MiP. However, the disparity between the high rates of women who attend antenatal care (ANC)10 and significantly lower rates of women who receive IPTp or an ITN point to insufficient provision of MiP commodities and services by providers.11

- World Health Organization. Malaria in Pregnant Women. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/high_risk_groups/pregnancy/en/. Accessed September 13, 2016.

- Roll Back Malaria, Malaria in Pregnancy Working Group. http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/files/files/working-groups/MiPWG/RBMMiPWG%20Infographic%2023May2016.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2016.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria for Pregnant Women (IPTp). Center for Disease Control and Prevention website: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/malaria_worldwide/reduction/iptp.html. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- World Health Organization. WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). 2014.

- World Health Organization. Eliminating Malaria. 2016.

- Hill et al. The contribution of malaria control to maternal and newborn health. Roll Back Malaria Progress and Impact Series No. 10. 2014.

- Roll Back Malaria Partnership. 2015 Global Call to Action. 2015.

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2015. 2015.

- Ricotta E, Koenker H, Kilian A, et al. Are pregnant women prioritized for bed nets? An assessment using survey data from 10 Africa countries. Glob Health Sci Pract. May 1, 2014; vol. 2 no. 2 p. 165-172. http://www.ghspjournal.org/content/2/2/165. Accessed September 13, 2016.

- UNICEF. Antenatal Care Coverage. http://www.data.unicef.org/maternal-health/antenatal-care.html. 2016.

- Hill J, Hoyt J, van Eijk AM, et al. Factors affecting the delivery, access, and use of interventions to prevent malaria in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013. 10(7), e1001488.

Why was this iKit created?

The Health Communication Capacity Collaborative's review of MiP SBCC strategies describes the structure and content of 5 country strategies and provides recommendations for improving MiP content.

Research has identified several barriers to the delivery and use of MiP prevention and treatment services in sub-Saharan Africa. These barriers occur at the individual, social, environmental and health system levels. A number of national and community-based social and behavior change communication (SBCC) initiatives have been implemented to address these barriers; however, their impact is limited by the fact that these efforts tend to focus only on the pregnant woman or her male partner. A 2015 President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) literature review of activities and programs designed to increase service provider adherence to MiP guidelines found few examples of SBCC activities targeting service providers, despite a growing body of evidence that healthcare workers’ attitudes are a key determinant to the use of MiP services.1

Moreover, many SBCC activities are not strategically developed, and miss opportunities to improve their reach and impact. A 2014 PMI review of MiP content in malaria communication strategies from five sub-Saharan African countries found a lack of documented formative research to inform priorities, as well as weak audience segmentation, unclear roles and responsibilities between national malaria control programs (NMCPs) and reproductive health programs, and inconsistencies between national malaria strategic plans and their supporting malaria communication strategies.2 This review found few examples of SBCC targeting service providers in national malaria communication strategies.

With these gaps in mind, this reference guide was developed to help SBCC and MIP program managers and stakeholders address some of these gaps and improve SBCC strategies and interventions for MIP, especially those interventions that target healthcare workers.

- Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. Interventions Targeting Health Workers to Improve Provision of Malaria in Pregnancy Services and Commodities: an SBCC Perspective. 2015.

- Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. Social and behaviour change communication in support of malaria in pregnancy control prevention. 2014.

Integration

The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program's Review of MiP issues highlights the need for better integration between national malaria control programs and reproductive health programs.

The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program's Review of MiP issues highlights the need for better integration between national malaria control programs and reproductive health programs.

MiP is a crosscutting issue that involves a variety of partners – from NMCP and reproductive maternal and child health units, ministry of health (MOH) technical working group members and leadership from health promotion and community services units. PMI teams and NMCP units are also likely to work in collaboration with reproductive, maternal, newborn and child (RMNCH) health specialists that are not focused exclusively on malaria. As readers go through this document, they should think of ways to collaborate with these stakeholders – public and private sector, those working at the national-level or policy level and those working at the regional-level, district-level or community level. Readers may find it useful to convene a stakeholder workshop when designing or updating a malaria communication strategy to encourage feedback and input from various perspectives and ensure buy-in from all relevant MOH units and implementing partners. It is often best to include these various partners in the creative strategy development process to identify blind spots and reduce inefficiencies.

How-To Guide Step-by-step guidance on integrating SBCC into service delivery programs

How-To Guide Step-by-step guidance on conducting a stakeholder workshop

Commodities, Supervision and Training

The assumption underlying any communication strategy is that the necessary service delivery, policy, management, logistics and supplies exist. Malaria communication programs cannot succeed if:- National protocols and service delivery guidelines are not adequately disseminated and understood

- The right commodities (e.g., artemisinin-based combination therapy – ACTs, long-lasting insecticide-treated net – LLINs, RDTs and SP) are not consistently available

- Service providers do not receive adequate training, oversight and supportive supervision. Utilize advocacy to move these forward when necessary

Conducting a Situation Analysis

ABOUT THIS SECTION

A growing body of evidence on MiP interventions highlights a number of considerations and lessons learned for designing and implementing MiP SBCC strategies. Conducting a situation analysis will provide a strong foundation of what is known about MiP at the global level as well as within a specific country’s social, economic, political and epidemiological context. To conduct a comprehensive situation analysis, review the following types of secondary data:

Global and national malaria guidance documents and policies

National health and demographic, facility, and epidemiological data

National and subnational malaria in pregnancy program materials and evaluations

Readers should review the data sources, case studies and considerations included in these sections to ensure that their situation analysis identifies the evidence-based approaches and lessons learned. This information will strengthen the MiP section of your malaria SBCC strategy. Considerations listed in the service provider and community sections are meant to help determine which factors are most influential. While some patterns exist across countries or regions, examples listed are intended to be ideas for inquiry, not representative truth. This section gives a brief list of national and subnational data to review to gain a deeper understanding of the context in which one is working.

Global Guidelines

The RBM, WHO and PMI have produced a number of global guidance documents and consensus statements that should be considered when conducting a situation analysis. Some of these resources are listed below.

Optimizing the Delivery of Malaria in Pregnancy Interventions (PMI, 2013): This consensus statement should be reviewed to ensure MiP priorities, interventions, monitoring and evaluation, and research are evidence-based and in line with priorities agreed on by global MiP stakeholders.

Optimizing the Delivery of Malaria in Pregnancy Interventions (PMI, 2013): This consensus statement should be reviewed to ensure MiP priorities, interventions, monitoring and evaluation, and research are evidence-based and in line with priorities agreed on by global MiP stakeholders.

WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (WHO, 2014): This policy brief contains the latest IPTp guidelines clarifying the method and timing of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) delivery. Use this brief to ensure IPTp guidance is accurate and up to date.

WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (WHO, 2014): This policy brief contains the latest IPTp guidelines clarifying the method and timing of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) delivery. Use this brief to ensure IPTp guidance is accurate and up to date.  Intermittent Screening and Treatment in Pregnancy and the Safety of ACTs in the First Trimester (WHO, 2015): This reference document provides recommendations on Intermittent Screening and Treatment in pregnancy (ISTp) and use of ACT in the first trimester. Consult this resource to understand why global stakeholders discourage ISTp as an alternative to IPTp-SP.

Intermittent Screening and Treatment in Pregnancy and the Safety of ACTs in the First Trimester (WHO, 2015): This reference document provides recommendations on Intermittent Screening and Treatment in pregnancy (ISTp) and use of ACT in the first trimester. Consult this resource to understand why global stakeholders discourage ISTp as an alternative to IPTp-SP.  Consensus Statement on Folic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy (RBM Partnership’s Malaria in Pregnancy Working Group, 2015): Refer to this consensus statement to ensure that folic acid is procured in doses that will not interfere with the SP. It also answers a number of frequently asked questions.

Consensus Statement on Folic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy (RBM Partnership’s Malaria in Pregnancy Working Group, 2015): Refer to this consensus statement to ensure that folic acid is procured in doses that will not interfere with the SP. It also answers a number of frequently asked questions. Service Provider Considerations

Research on service providers has identified a number of factors that could influence MiP services uptake and provider adherence to guidelines. Review these factors for applicability to the local context. These are not meant to be a comprehensive list of behavior determinants, but consist of examples taken from recent work. Recent program reports and research found the following factors:

How-To Guide Step-by-step guidance on service provider behavior change

Community Considerations

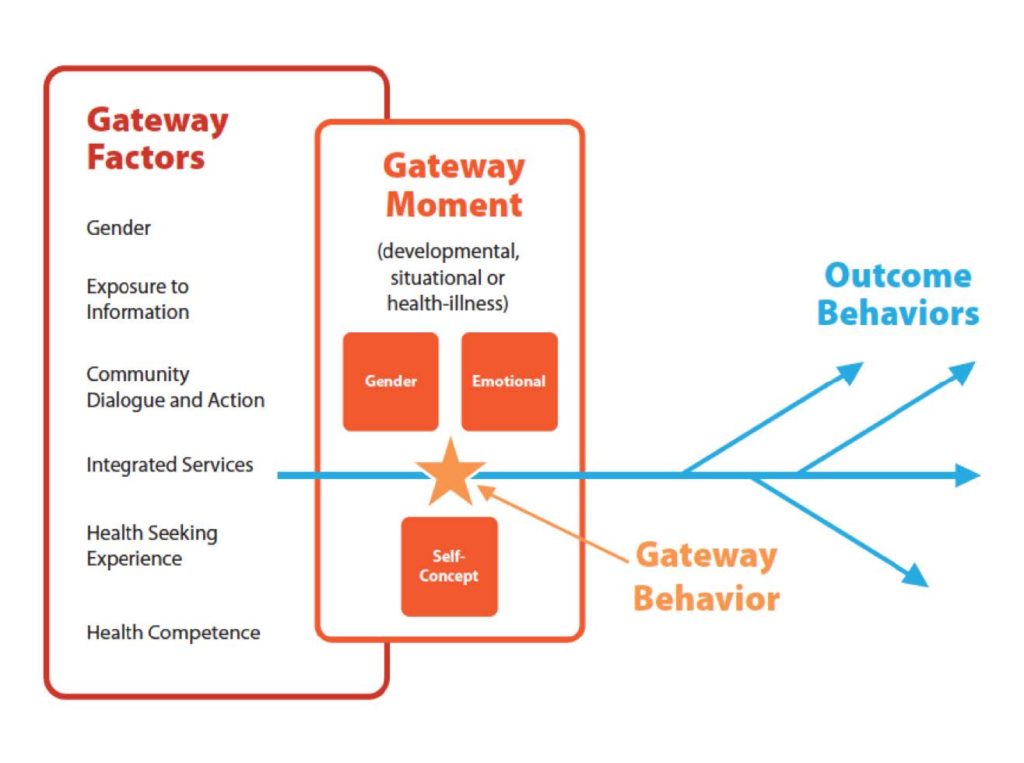

There are a number of community-level factors that have been shown to influence the use of MiP interventions. As with the service provider considerations, primary or secondary research should be used to determine which factors a a communication strategy will need to address. Some of these may include awareness, social support, response-efficacy, self-efficacy, attitudes and perceived risk. Read more about a new line of inquiry, Gateway Behaviors, below.

Local Context

Analyzing global, national and sub-national data sources should give planners an understanding of what has happened to date, but there may be areas to learn more. If knowledge gaps have been identified (e.g., community and service provider knowledge and attitudes), it may be necessary to conduct further qualitative and/or quantitative research on the issues.

Qualitative research might take the form of focus group discussions among pregnant women and those who influence their health behaviors and care-seeking decisions. Key informant interviews with gatekeepers and providers such as community drug vendors, traditional birth attendants, facility-based service providers and community workers can provide invaluable information about what people do, why they do it and the obstacles to address to affect positive behavior change. Findings should also inform how to best formulate messaging and choose appropriate channels.

Quantitative research may include household surveys with the target audience, as well as other populations who might influence their healthcare-seeking behaviors. The BCC Indicator Guide, developed by the RBM Partnership, contains a list of standard behavioral indicators and appropriate prioritization of those indicators. These questions can be asked both at the beginning of a program during the formative research phase, as well as at the end of a program during the assessment phase.

| Data source | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Malaria Indicator Survey |

|

| Demographic Health Survey |

|

| Multiple Cluster Indicator Survey |

|

| Data source | Indicators | Health Management Information System and or DHIS 2 |

|

|---|---|

| Patient exit interviews

|

|

| In-service training or supportive suppervision in-depth interviews and or focus groups |

|

Situation: According to a 2013 malaria SBCC survey, less than one fifth of Liberians responded that they had discussed the issue of malaria in pregnancy (MIP) with spouses or friends in the last year. The majority of those surveyed felt that most women attend at least four ANC visits. Many women asked about IPTp expressed doubt that taking it would reduce their chances of getting malaria during their pregnancy. In this survey, the most important source of information about IPTp was service providers (mentioned more frequently as a source than radio). Liberia Technical Guidelines for MIP 2015 states that pregnant women do not attend as many ANC visits as they could, and often show up late in their pregnancy. Many do not arrive with their ANC card in hand. DHS data indicates that less than half of pregnant women received two or more doses of SP by 2013. This proportion has remained almost unchanged since 2011.

Situation: According to a 2013 malaria SBCC survey, less than one fifth of Liberians responded that they had discussed the issue of malaria in pregnancy (MIP) with spouses or friends in the last year. The majority of those surveyed felt that most women attend at least four ANC visits. Many women asked about IPTp expressed doubt that taking it would reduce their chances of getting malaria during their pregnancy. In this survey, the most important source of information about IPTp was service providers (mentioned more frequently as a source than radio). Liberia Technical Guidelines for MIP 2015 states that pregnant women do not attend as many ANC visits as they could, and often show up late in their pregnancy. Many do not arrive with their ANC card in hand. DHS data indicates that less than half of pregnant women received two or more doses of SP by 2013. This proportion has remained almost unchanged since 2011.

SBCC emphasis: Taken as a whole, this survey data suggests that SBCC activities at the community level should aim to increase knowledge about MIP, promote positive attitudes regarding the efficacy of IPTp, and emphasize interpersonal communication within the family and with friends about IPTp. CHVs and TTMs should encourage early and regular ANC attendance, and remind pregnant women to demand both SP and LLINs. At the facility level, service providers (the most frequently cited source of information regarding IPTp) should be encouraged to counsel pregnant women on the importance, safety, and efficacy of IPTp.

Beyond awareness, these interventions should seek to to address response-efficacy (confidence in the effectiveness) of IPTp among pregnant women, and to to increase self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability) to attend ANC early and every month thereafter. Benefits of ANC should be emphasized. Family and friends of pregnant women should be encouraged to discuss the importance of ANC attendance with them. Service provider self-efficacy to provide counseling to pregnant women during each and every ANC consultation must also be raised.

In Tanzania, the Safe Motherhood campaign was originally designed as a MiP initiative but eventually expanded to include a broader range of safe motherhood behaviors. Formative research indicated that women in Tanzania were arriving at ANC late and not frequently enough. A culture of secrecy surrounding pregnancy, and distance from health facilities, were the other key behavioral determinants discovered. To address this, the second phase of the campaign demonstrated ways couples could “show their love,” modeling both partners traveling to and attending ANC.

In Tanzania, the Safe Motherhood campaign was originally designed as a MiP initiative but eventually expanded to include a broader range of safe motherhood behaviors. Formative research indicated that women in Tanzania were arriving at ANC late and not frequently enough. A culture of secrecy surrounding pregnancy, and distance from health facilities, were the other key behavioral determinants discovered. To address this, the second phase of the campaign demonstrated ways couples could “show their love,” modeling both partners traveling to and attending ANC.

Problem: Providers do not welcome clients according to standards

Problem: Providers do not welcome clients according to standards