+ 123 456 7890

Background and Justification

SSFFC malaria medicines are a unique public health issue that varies from country to country. This widespread problem is associated with a number of public health risks, and requires a deep understanding of purchasing and vending practices. The growing body of knowledge on SSFFC malaria medicines points to a number of risks and protective factors that SBCC professionals should keep in mind.

Why Use Advocacy and SBCC To Combat SSFFC Malaria Medicines?

While activities aimed at improving international and national medicine manufacturing, procurement, regulation and enforcement (described here and here) can greatly reduce the burden of SSFFC antimalarials in the long run, they cannot eliminate the problem entirely – or protect today’s malaria medicine consumers from the dangers of SSFFC medicines. However, there are steps that individuals, families, communities and specialty agencies (such as regulatory and law enforcement agencies) can take. This is where SBCC and advocacy are important.

SBCC is the science and art of using communication to change individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, behavior and social norms for better health and/or development outcomes. SBCC can improve public awareness about SSFFC malaria medicines and influence individuals’ behavior so that they protect themselves, their families and their communities, while changes to systems and policies are put in place.

SBCC contributes to the fight against SSFFC malaria medicines in a number of important ways:

- Improving consumers’ knowledge of the harm caused by SSFFC medicines, as well as the steps that they can take to protect themselves and their families.

- Convincing pharmacists of the dangers of diverted, poorly stored and unregulated medicines, and their responsibility for the safety of their customers.

- Changing customers' attitudes so that they value, and feel capable of influencing, the quality of malaria medicines they use.

- Encouraging consumers to take protective actions that reduce their risk of buying poor quality malaria medicines, and reporting to proper authorities when they feel that they have purchased poor quality medicines.

- Inspiring informal vendors to protect their customers by buying medicines from reputable sources and storing them according to recommendations.

- Encouraging leaders, pharmacists, health workers, drug vendors and the public to report suspicious activity to national and international surveillance and law enforcement bodies, such as the U.S. government’s “Make a Difference” (MAD) Malaria Hotline.

Advocacy operates at the political, social and individual levels and works to mobilize resources and political and social commitment for changes in systems, laws and policies. Advocacy aims to create an enabling environment at any level, including the community level (e.g. traditional government or local religious endorsement), to ask for greater resources, encourage the equitable allocation of those resources and remove barriers to policy implementation. Guidelines for advocacy as a process are provided in the ASK Approach.

Advocacy is important to the fight against SSFFC malaria medicines in a number of ways:

- Raising decision-makers’ awareness of SSFFC malaria medicines so that priority is placed on developing and implementing policies to protect consumers.

- Influencing customs and immigration officials to work more closely with drug regulatory and law enforcement agencies to stop importation of SSFFC malaria medicines.

- Convincing law-makers to strengthen penalties for procuring, importing, manufacturing and selling SSFFC malaria medicines.

- Making a case for improving quality assurance and surveillance systems for malaria medicines.

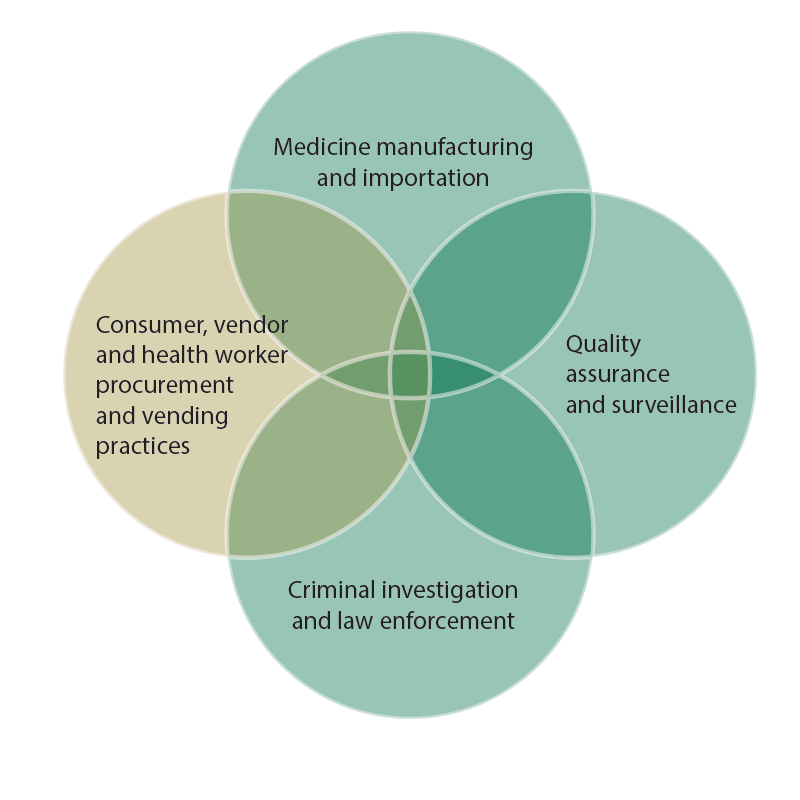

Most SBCC strategies to address SSFFC malaria medicines employ a combination of advocacy and SBCC. The relationship between advocacy, SBCC, manufacturing, procurement, enforcement and regulation are depicted in the figure below. The yellow circle shows the areas where SBCC is most important. The green circles show areas where advocacy is important. The SBCC and advocacy circles overlap, showing that SBCC to change supplier and consumer procurement and vending practices can also influence and be influenced by the quality of enforcement, regulation and manufacturing. For example, when consumers only purchase malaria medicines that have been approved by the regulatory body, many manufacturers and importers will stop producing unregulated medicines, and regulators will feel pressure to improve quality assurance and surveillance systems.

Consequences of SSFFC Malaria Medicines

Poor quality medicines create a ripple effect that goes far beyond an individual’s health. For example:

SSFFC antimalarials seriously threaten national healthcare systems.

Spending public money on SSFFC medicines is a waste of the limited financial resources reserved for malaria and health. This inefficiency is particularly problematic for countries already suffering from limited health resources and weakened infrastructure – which is the case for many countries where SSFFC antimalarials are found.

SSFFC antimalarials negatively influence client perceptions and behavior.

Poor quality medicines can negatively influence the way that clients think about the quality of their healthcare system and treatment options. For example, a malaria-positive client who does not get better after taking malaria medicines may become frustrated and distrusting of malaria medicines or the health system in general. They could decide that it is not worth the effort and resources required to seek healthcare from the formal, regulated health system, and self-medicate through the informal, unregulated sector.

SSFFC antimalarials increase global malaria deaths through artemisinin resistance.

Taking too little of the active ingredient in malaria medicine can build resistance to that drug among malaria parasites. Resistance to monotherapies like chloroquine have been documented in East and West Africa, Southeast Asia and South America since the 1950s. Researchers have already identified several areas where the malaria parasite is resistant to artemisinin, the active ingredient in the current first-line treatment for malaria. Because no alternative malaria medicine is expected to enter the pharmaceutical market in upcoming years, increased artemisinin resistance will lead to more malaria deaths.

Prevalence of SSFFC Malaria Medicines

No country is unaffected by poor quality medicine, especially with the expansion of Internet medicine vendors. While SSFFC medicines can be found in both developed and developing countries alike, their presence is strongest in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia with weak regulatory and enforcement systems. Some experts have estimated that SSFFC medicines' presence ranges from one percent in the developed world to 50 percent in the developing world. However, a validated estimate of the global prevalence of SSFFC malaria medicines does not exist, due to the lack of universally-accepted medicine quality definitions.

Malaria medicines are particularly prone to quality issues, because they are in high demand in malaria endemic countries. According to recent studies, approximately one in ten doses of malaria medicines found in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are poor quality. The majority of these medicines were substandard, not falsified, containing inadequate active ingredients to treat malaria.

Studies also show that the amount of SSFFC antimalarials can vary within a country, and that customers who buy their medicines from informal vendors are at higher risk of purchasing SSFFC malaria medicines than those who get them from government health services. This difference is due to the higher concentration of SSFFC antimalarials in the unregulated private sector, compared to the regulated public sector. Unfortunately, many people in rural areas live far from public sector health facilities and must rely on unregulated private sector vendors for their malaria medicines.

One of the primary barriers to developing a strategy around SSFFC medicines is that the majority of poor quality medicines are thought to originate from countries that are also the largest producers of good quality medicines. While weak manufacturing and regulation create challenges, a lack of health leadership and decision-makers to address this problem, porous borders, corruption and manufacturers' technical sophistication to produce SSFFC medicines also serve as obstacles.

Factors Influencing SSFFC Antimalarial Vending and Purchasing Practices

There are a number of factors that influence the selling and purchasing of SSFFC medicines, but the influence of each varies from country to country. It is important to consider all of these elements when developing an SBCC strategy around malaria medicines to ensure the selected approach is effective in promoting change and programs are reaching appropriate audiences.

There are a number of factors that influence the selling and purchasing of SSFFC medicines, but the influence of each varies from country to country. It is important to consider all of these elements when developing an SBCC strategy around malaria medicines to ensure the selected approach is effective in promoting change and programs are reaching appropriate audiences.

In many cases, consumers are looking for low-cost medicine that does not require much effort to obtain. Access and cost of ACTs may drive consumers to shop for medicines in the unregulated private sector, where medicine is more likely to be low quality. It is also common for patients to self-treat with malaria medicine without first getting tested or consulting a health provider. Those who self-treat sometimes do so with poor quality medicine (often monotherapies) purchased from informal medicine vendors. While many know about the presence of substandard or diverted medicine, acceptance and normalization of the informal sector may stop shoppers from viewing these vendors as risky or dangerous. The convenience of buying from the informal sector, as well as the desire not to betray their networks, may prevent consumers from wanting to report suspected SSFFC medicine vendors.

On the other hand, the attitudes and behaviors of providers and medicine vendors also play a role in medicine purchasing. Many countries’ medicine supply chains include informal medicine vendors, who are business owners by trade and do not have a proper health education. As such, they may be more motivated by making a profit than by promoting best health practices. For example, research in Nigeria found that informal vendors were heavily influenced by pleasing the customer. Customers usually told the vendor what medicine they were looking for and the vendor would often sell it without asking any questions or suggesting other options. Additionally, both health providers and informal vendors in Nigeria reported that their recommendations were influenced by their perception of a customer’s ability or willingness to pay for a particular medicine type or dose.