+ 123 456 7890

Country Examples

Nigeria, Ghana and Benin are just some of the countries that are working to reduce SSFFC malaria medicines. Click on areas below to learn more about each country and/or region.

Nigeria

The prevalence of SSFFC malaria medicines in Nigeria has a great impact on global malaria morbidity and mortality, as the country has more reported malaria cases and deaths than any other country in the world.

Agents of NAFDAC (National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control) in Shagamu, Ogun state, Nigeria, publicly destroy fake, substandard, unwholesome and expired pharmaceuticals, food and consumables worth N249,406,119.20 seized at different ports of entry nationwide and from street drug hawkers. © 2007 Opara Adolphus, Courtesy of Photoshare

After a 2001 study estimated that 40 percent of medicines in the Nigerian market were substandard or falsified, NAFDAC, under former Director General Dora Akunyili, prioritized the fight against SSFFC antimalarials in Nigeria. The agency took hard action – retraining NAFDAC staff, opening up more state offices, updating drug analysis laboratories and creating stricter drug regulations. Public awareness campaigns used TV and radio programs, National Youth Service Corps groups, food and drug safety education in schools and a consumer care hotline to raise public awareness of the problem. While SSFFC medicines continue to affect the country, their presence has significantly dropped. One recent study in Enugu city, Nigeria even found that approximately 6 percent of medicines were substandard and 1 percent were falsified.

Today, Nigeria continues to be challenged by its limited availability of healthcare facilities and its large, informal, unregulated private sector. Consumer behavior also makes regulation difficult. About half of all Nigerians live in rural areas, far from government health facilities, and rely on traditional open-air markets and untrained patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) for malaria treatment.

Government agencies and the pharmacist council have tried to close down some of Nigeria’s larger open drug markets – the government is currently increasing the availability of good quality drugs by opening large government-run wholesale distribution centers.

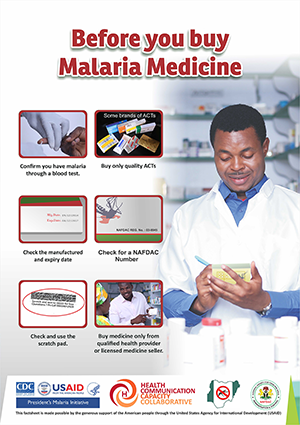

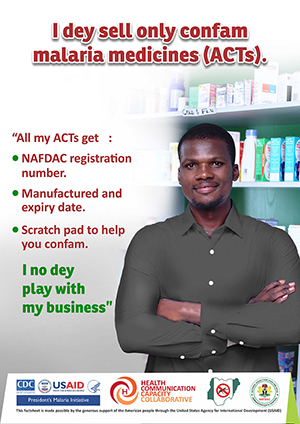

NAFDAC has made Mobile Authentication Service (MAS) mandatory for all ACTs. When the scratch technology was first launched it was accompanied by an awareness-raising campaign, but experts have found that the consumer education piece must be continued and expanded for the technology to be effective.

In 2016, HC3 partnered with the NMEP and NAFDAC to launch a five-month SBCC campaign in Awka Ibom State to promote practices that reduce consumers’ risk of using SSFFC malaria medicines. The campaign combined house-to-house visits by community volunteers, TV and radio spots (spot 1 | spot 2) and print materials, training for PPMVs and media engagement through journalist trainings and mentoring. Print materials included advocacy fact sheets, a fact book and posters for PPMVs, as well as those educating clients about steps they can take to protect themselves and how to verify the quality of their program using their mobile phone. See a copy of the SSFFC malaria medicines communication strategy for Nigeria here.

Ghana

Malaria is a leading cause of death in Ghana. Unfortunately, the country is also plagued with unregulated drug markets and poor regulation compliance. While not representative of the entire drug market, a convenience sample in 2008 found that one in three malaria medicines were substandard or falsified. Another study from 2011 found that 37 percent of medicines were substandard and no falsified medicines.

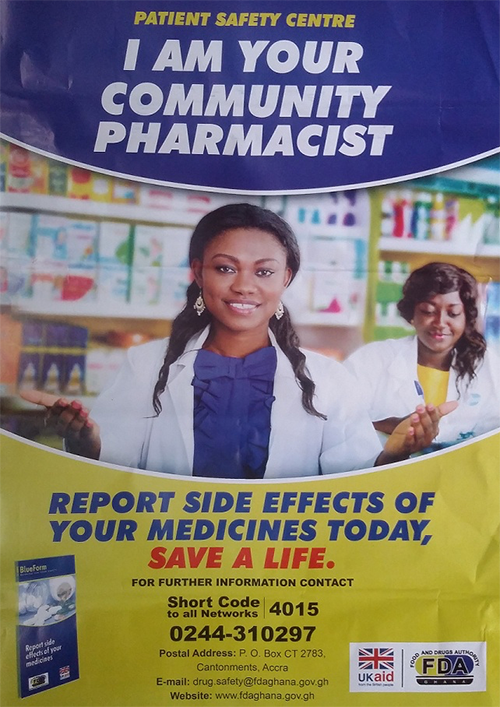

This poster encourages consumers to report adverse side effects to a national hotline. For more information on this campaign, see here.

The Ghanaian Food and Drugs Authority, in collaboration with USP, have been undertaking countrywide product quality monitoring exercises to determine the quality of antimalarials on the Ghanaian market since 2008. Results of the monitoring exercise indicate a steady drop in the incidence of SSFFC antimalarials from as high as 28 percent in 2008 to three percent in 2015. The most recent round of quality tests in 2015 found no substandard ACTs, although there were some failed malaria medicines that were not ACTs.

Ghana houses one of four Official Medicines Quality Control Laboratories in Africa. The others are located in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Kenya. USP’s Center for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training (CEPAT), based in Ghana, trains pharmaceutical professionals from across Africa in medicine evaluation and registration, quality control and good manufacturing practices.

Benin

Malaria is the leading cause of death in Benin for pregnant women and children under five. The national policy regulated by the Direction des Pharmacies et du Medicaments (DPMED) is to treat simple malaria using ACTs.). The DPMED is in charge of controlling the quality of medicines before they are released into the market and inspects pharmacies annually.

Moment from TV spot to raise awareness of SSFFC malarial medicines and promote safe medicine sources. Translation: “Every five minutes, a child dies because of fake antimalarial medicines, namely fake ACTs bought from informal shops and vendors.”

Unfortunately, a 2009 study found that half of antimalarial medicines were substandard or falsified. A 2011 ACTwatch study study found that general retailers were the most common type of outlet carrying malaria medicines in Benin, compared to public and not-for-profit sources. The study also revealed a troubling contrast between the availability of high quality ACTs in the public/not-for-profit and private sectors – 86 percent vs. 23 percent.

The Government of Benin working together with its partners increased the availability of good quality ACTs, installed a national quality control laboratory, created the Technical Commission for Registering Medication, conducted routine stock inspections and has plans to close down Cotonou’s popular illegal medicine market zones located in “Dantokpa.”

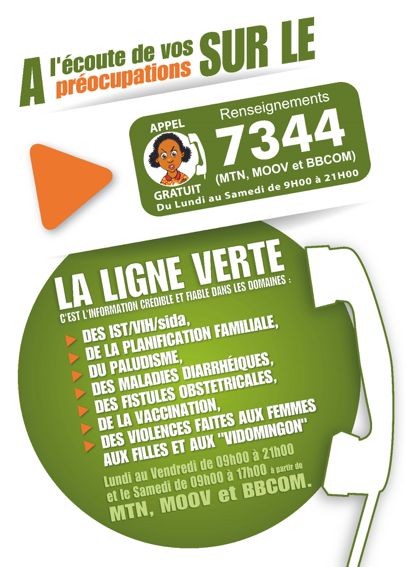

The Beninese Ministry of Health and the Beninese Association of Social Marketing (ABMS) created a national hotline to report information on suspicious activities and medication, and launched a six-month renewable mass-media and interpersonal communication campaign to increase awareness of SSFFC malaria medications .

The campaign used TV spots, stickers, house-to-house outreach activities and journalist training to raise awareness about the dangers of SSFFC malaria medicines, as well as the availability of the free malaria services provided through the public health sector. The campaign also provided the opportunity to engage vendors who sell ACTs in markets around the importance of medicine quality. The campaign reached a total of 776 vendors and 2,482 clients through peer educators and 15703 mothers of children under five by interpersonal communication.

Greater Mekong Subregion

Over the past 15 years, the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), comprised of the People’s Republic of China, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PRD), Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, has made positive strides in malaria prevention and control. In fact, GMS governments, with unprecedented donor and political support, have pledged to eliminate malaria from the region by 2030. However, the development and spread of artemisinin resistance threatens this progress. The widespread prevalence of SSFFC malaria medicine in the GMS only increases the threat of resistance, as exposure to substandard doses of artemisinin strengthens parasites’ tolerance to various antimalarial medicines. Self-medication is also very common among residents, mobile and migrant populations, which creates challenges for health practitioners who want to track whether consumers are buying quality products and taking the full dose.

While the prevalence of SSFFC malaria medicine in the GMS varies depending on the country, it is clear that antimalarials from the informal private sector are likelier to be poor quality than those available through the formal health system. This is especially the case in areas near international borders with unofficial entry points that are harder to regulate. A multi-country study conducted from 1999 to 2000 using convenience sampling identified SSFFC antimalarials in five countries, finding fake artesunate in 25 percent of samples from Cambodia, 38 percent from Lao PDR, 40 percent from Myanmar, 11 percent from Thailand and 64 percent from Vietnam. Another study from 2006 found that both licensed and unlicensed outlets in the GMS were selling SSFFC malarial medicines (50 percent of licensed and 75 percent of unlicensed outlets). A more recent study (2013) had a 4.9 percent failure rate among antimalarial samples from the GMS – which shows that while some progress has been made, there is still a ways to go.

This progress is due to the numerous programs that were put in place to combat SSFFC antimalarials in the GMS, including activities aimed at increasing surveillance, education and access to quality-assured medicines. Efforts like the WHO database allow for quick data sharing when suspected SSFFC medicine cases are identified. The USP has worked with local governments to create a Network of Official Medicine Control Laboratories to improve quality surveillance and promote experience exchange among regulators. The Promoting Quality Medicines program has also produced a series of public service announcements (PSAs) to warn the public about poor quality medicine, as well as a documentary about SSFFC medicines in the region. Additionally, projects like the USAID-supported Control and Prevention of Malaria (CAP-Malaria) implemented by University Research Co., LLC. (URC) Cambodia and Myanmar to standardize surveillance and treatment protocols, and promote positive case management and medicine use through trainings and educational materials for consumers, health providers, pharmacists and medicine vendors.

A volunteer Village Malaria Worker conducts Malaria Direct Observe Therapy (DOT) in Roveang village, Sotnikum district, Siem Reap province, Cambodia.© 2012 Lina Kharn/University Research Co., LLC, Courtesy of Photoshare

Cambodia has taken a particularly strong national stand to promote quality ACT. It was the first country to change its national medicine policy to ACTs, and has since banned monotherapies. In 2003, before the monotherapy ban, PSI launched a national social marketing program to provide subsidized quality-assured ACTs and RDTs to private sector health providers with monthly supportive supervision visits. Mass media channels and mobile video units at the village level were used to stress the importance of getting tested before taking treatment, the dangers of substandard drugs and the importance of completing the full three-day course. As caseloads have declined and the disease has become more concentrated, so has the network. The project currently targets registered providers and at-risk worksites employing mobile migrants in the north and northeast of the country where the prevalence is highest. Moreover, as a part of the Malaria Control in Cambodia (MCC) project, CAP-Malaria (October 2007 to September 2011) and the follow-on CAP-Malaria project (October 2011 to September 2016) – both implemented by URC and the Cambodian government launched its “village malaria workers” (VMW) program, which identified and trained VMWs (two per village), and provided them with free RDTs and quality-assured antimalarial medicine. The program identified and trained VMWs (2 per village), provided them with free rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and quality-assured antimalarial medicine, and trained them to provide directly observed treatment (DOT) of Plasmodium falciparum malaria to ensure complete treatment and cure. This program not only helped to “move malaria treatment from the private to the [quality-assured] public sector,” it also reduced the use of SSFFC medicines. Trainings introduced VMWs to information about the symptoms of malaria, ways to prevent mosquito bites and the dangers of SSFFC medicines. These messages were also disseminated to the public through posters, billboards and a call-in radio show. Through the PQM program the Cambodian government created a joint committee to reduce the volume of SSFFC medicines in Cambodia. These efforts have helped produce promising results. A 2013 quality study did not find any falsified malaria medicines. However, 31.3 percent of samples were found to be substandard and 10 percent were expired.

Significant work is also being done in Myanmar. In 2012, PSI assessed the availability of different antimalarials sold by Myanmar’s private sector health outlets through a market survey and found that an alarming 70 percent of outlets were carrying oral artemisinin monotherapy. This finding triggered the Artemisinin Replacement Program, which replaced monotherapies with a branded quality-assured ACTs called Supa Arte, supplied by PSI. Supa Arte, has a quality-assured logo (a golden lotus) printed on all packaging. In 2013, market coverage was increased using a second distributor (Artel+). Market surveys, completed every year since the start of the program, have documented the dramatic and rapid decline of monotherapy availability from 70 percent (2012) to 50 percent (2013) to 10 percent (2014). The AMTR network currently has 20,000 supported outlets who are stocked with quality assured ACTs and RDTs and routinely visited to ensure correct malaria case management and regular data reporting. Additionally, CAP-Malaria has expanded access to quality malaria medicines throughout the Myanmar health system by working with employers to train informal private providers and provide them with quality-assured RDTs and malaria medicines. These informal private providers – also known as “quacks” – are often the first place villagers go to seek treatment, due to their low cost and easy accessibility. To combat artemisinin drug resistant malaria in Myanmar, CAP-Malaria piloted DOT administration of ACTs for Plasmodium falciparum cases by VMWs. URC is applying the lessons learned from these efforts to expand the engagement of informal private providers and VMWs in malaria diagnosis and DOT administration of ACTs in the follow-on project PMI|USAID Defeat Malaria (October 2016 to September 2021) in Myanmar.

REMEMBER! Because SSFFC problems vary from country to country, campaigns and activities that worked in Senegal and Benin may not be effective in your country. For example, mobile verification systems and messages may not be effective in countries where medicine diversion is the primary problem, as the medicine likely started off genuine but has deteriorated during illicit transport. We encourage you to take inspiration from the examples shown here, but then choose a communication strategy and target audience based on the unique needs and resources available in your country. See Part 3 for guidance on how to develop and implement an SBCC campaign tailored for your country. If you have also conducted SBCC campaigns for SSFFC antimalarials but do not see your work here, contact us for ways to share your materials, experiences and lessons learned.

Visit the Global SSFFC Malaria Medicine Resources page to learn more.