SBCC and Gender: Models and Frameworks

- How do SBCC and gender theories relate to these frameworks? For example, how does ”power” within families, communities and social structures influence behavior?

- What kinds of health and gender-related outcomes is your program looking to achieve?

- How does gender affect access and utilization of health service delivery interventions?

- What kind of intervention, or combination of interventions, are most likely to lead to gender transformative behaviors?

- How do we anticipate that women and men will understand the program messages or activities differently?

- How, if at all, do we anticipate these answers will differ for sub-groups of men and women such as those from lower income groups or with less education?

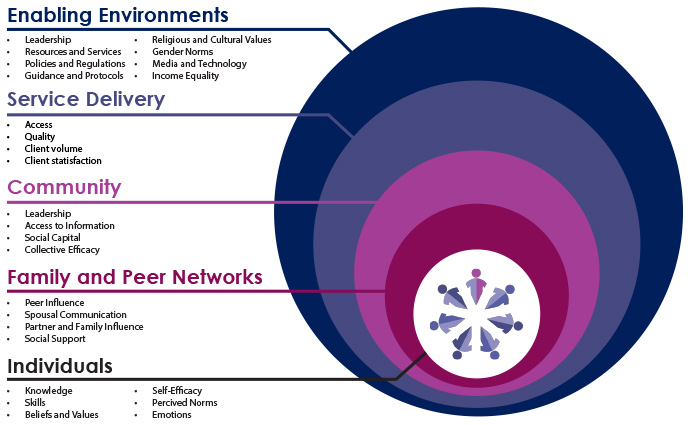

Socio-Ecological Model

A person’s behavior is influenced by many factors both at the individual level and beyond. The levels of influence on behavior can be summarized by the socio-ecological framework. This framework recognizes that behavior change can be achieved through activities that target four levels: Individual, interpersonal (family/peer), community and social/structural.

Go Girls! Initiative

Structural:

- School personnel training (“Go Teachers!”)

- Strengthening economic opportunities for vulnerable girls and their families

- Cross-sectoral fora.

Community:

- Community mobilization (“Go Communities!”).

Families and Social Networks:

- Adult-child communication skills training (“Go Families!”).

Individual:

- Life skills training for out-of-school girls (“Go Girls!”)

- School-based life skills training for girls and boys (“Go Students!”).

Cross-cutting:

- Reality radio programming.

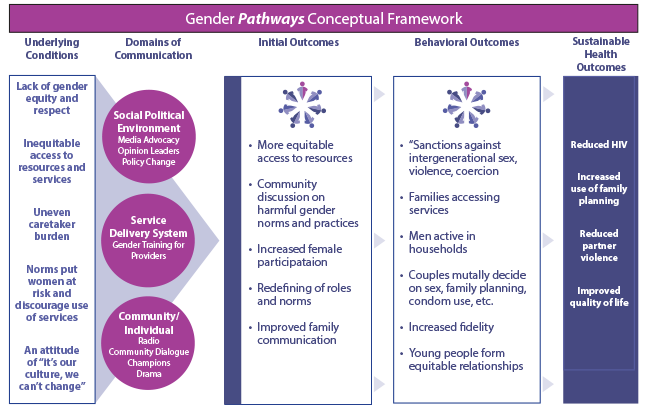

Pathways

Pathways™ provides a powerful framework to design health communication programs. It describes a process of social change that can be influenced by communication in a variety of ways depending on the goals a program sets for itself. The process is grounded in underlying social, political and economic conditions, and is expressed through three domains of communication and action: the social political environment, health service delivery systems and communities – and individuals within them– that attempt to manage their health. The Pathways™ framework charts the continuum of change, ensuring that a program addresses not only the immediate drivers of change, but also the contextual factors that determine sustained health outcomes.

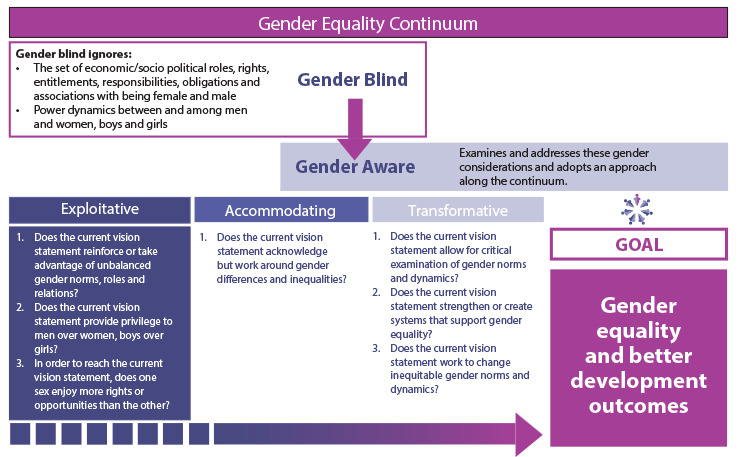

Gender Equality Continuum

Behavior change communication programs generally fit along the Gender Equality Continuum (IGWG, 2013), which can be used as a planning framework or as a diagnostic tool. As a planning framework, it can be used to determine how to design and plan interventions that move along the continuum toward transformative gender programming. As a diagnostic tool, it can be used to assess if, and how well, interventions are currently identifying, examining and addressing gender considerations, and to determine how to move along the continuum toward more transformative gender programming.

The continuum shows a process of analysis that begins with determining whether interventions are gender blind or gender aware. Gender blind policies and programs ignore gender considerations. They are designed without any analysis of the culturally defined set of economic, social and political roles, responsibilities, rights, entitlements, obligations and power relations associated with being female and male, or the dynamics between and among women and men, girls and boys.

Gender aware policies and programs examine and address the set of economic, social and political roles, responsibilities, rights, entitlements, obligations and power relations associated with being female and male, and the dynamics between and among women and men, and girls and boys.

The process then considers whether gender aware interventions are exploitative, accommodating or transformative.

Exploitative Gender Programming

These policies and programs intentionally or unintentionally reinforce or take advantage of gender inequalities and stereotypes in pursuit of project outcomes. This approach is harmful and can undermine program objectives in the long run.

Example:

To improve male involvement in family planning, a program used messages that relied on sports images and metaphors that encouraged winning, being in control of one’s life and making decisions. Impact evaluation showed that men interpreted the messages as promoting the notion that men alone should make family planning decisions. These messages unintentionally undermined the objectives of shared decision-making, improved couple communication and men as supportive partners (PRB, 2009).

Accommodating Gender Programming

These are policies and programs that acknowledge, but work around, gender differences and inequalities to achieve project objectives. Although this approach may result in short-term benefits and realization of outcomes, it does not attempt to reduce gender inequality or address the gender norms that contribute to the differences and inequalities. Gender accommodating approaches can be an important first step for some programming, such as when facing constraints on resources.

Example:

While trying to improve safer sex among commercial sex workers (CSW), a program had brothel owners demand 100 percent condom use in their brothels. Although the program helped increase condom use among CSWs and their clients, the power dynamics of negotiation between CSWs and their clients were not challenged (PRB, 2009).

Example: While trying to encourage a community to abandon the practice of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), a program engaged women, men, girls, boys and community leaders to examine the existing gender norms and beliefs leading to the practice of FGM/C. Challenging these norms helped the community identify a healthy and empowering coming of age ritual for young girls to replace FGM/C (PRB, 2009). Transformative Gender Programming

- Programs must never be gender exploitative. Such programs violate the public health principle of “first, do no harm.” While some interventions may be or contain elements that are (intentionally or unintentionally) blind, the aim should always be to move them toward accommodating, or ideally, transformative approaches.

- Programs should ultimately work toward transforming gender roles, norms and dynamics for positive and sustainable change.