Challenge

Service communication activities often require partnership and coordination. As described in the coordination section often a social and behavior change communication (SBCC) organization collaborates with a service delivery organization to develop communication that will contribute to improving health outcomes. Coordination has to occur before service delivery to generate demand for services, during service delivery to ensure that supply/services meet demand and that messages are harmonized, and after service delivery to support behavioral maintenance when clients are out of the clinical environment.

Response

With most productive partnerships, coordination among actors in service communication should leverage the comparative advantages of each partner, expanding their scope and reach. Formal arrangements such as memoranda of understanding and coordination mechanisms such as regular planning meetings operationalize the partnership and clarify roles and responsibilities. Joint planning and execution is of particular importance for campaign-style communication efforts and multi-year campaigns.

Coordination of service communication requires participatory processes that include intended populations in strategy development, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E). This will ensure that messages are well understood (including the rationale for sequencing and selection of channels), that activities are collaboratively planned and executed, and that monitoring allows partners to adjust activities and messages based on field experience. Joint evaluation can document the impact/relationship/influence of communication on service delivery.

Case Study: Stop Malaria Project – Uganda

Challenge

Challenge

Due to high rates of malaria and a lack of affordable testing facilities, health programs in Uganda have told providers and caregivers to treat all fevers as malaria for more than a decade. With uptake of prevention measures such as indoor residual spraying and long-lasting insecticidal nets, malaria incidence has dropped, but presumptive treatment continues. This has made over-diagnosis of malaria an increasing concern. The 2011 Demographic and Health Survey showed that only 26 percent of children under 5 with fever were tested for malaria, while 46 percent received treatment with artemisinin combination therapy (ACT). Ninety-six percent of those who tested positive for malaria received an anti-malarial, but so did 48 percent of those who tested negative. This means that frontline antimalarial drugs (ACTs) were being over-prescribed, resulting in stock-outs for those who actually needed the drugs. Unnecessary ACT also risks creating resistance to artemisinin-based treatments – already the case with quinine-based treatment.

Identifying the true cause of fever could lead to more effective treatment and ultimately better health outcomes. In 2012, the Government of Uganda adopted World Health Organization guidelines recommending that all individuals exhibiting malaria symptoms be tested and that only those who test positive receive malaria treatment. The National Malaria Strategic Plan 2011-2015 aimed to ensure that 90 percent of all suspected malaria cases in Uganda are tested before treatment is initiated.

Unfortunately, many providers continue to rely on their own clinical judgment and experience rather than on diagnostic tests, and treatment is often given to patients with negative test results. Providers’ reasons range from distrust of test results, lack of confidence in diagnosing and treating non-malaria fevers, and perceived or actual patient demand for malaria medicine, despite test results. Qualitative research has suggested a need for clear guidelines, a supportive environment, trust in the capacity of the laboratory staff or equipment, and the skills to manage fevers and navigate patient expectations to ensure the adoption of parasite-based treatment.

Response

The USAID-funded Stop Malaria Project (SMP), led by Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP), collaborated with the Ugandan government and multiple health partners to design and execute the “Test and Treat” campaign. The campaign sought to 1) build trust in malaria test results among clients and health providers; 2) increase the proportion of clients with fevers who are treated appropriately; and 3) encourage community members to get children under 5 tested for malaria before treatment. The campaign was rolled out in 24 health districts where malaria is highly endemic.

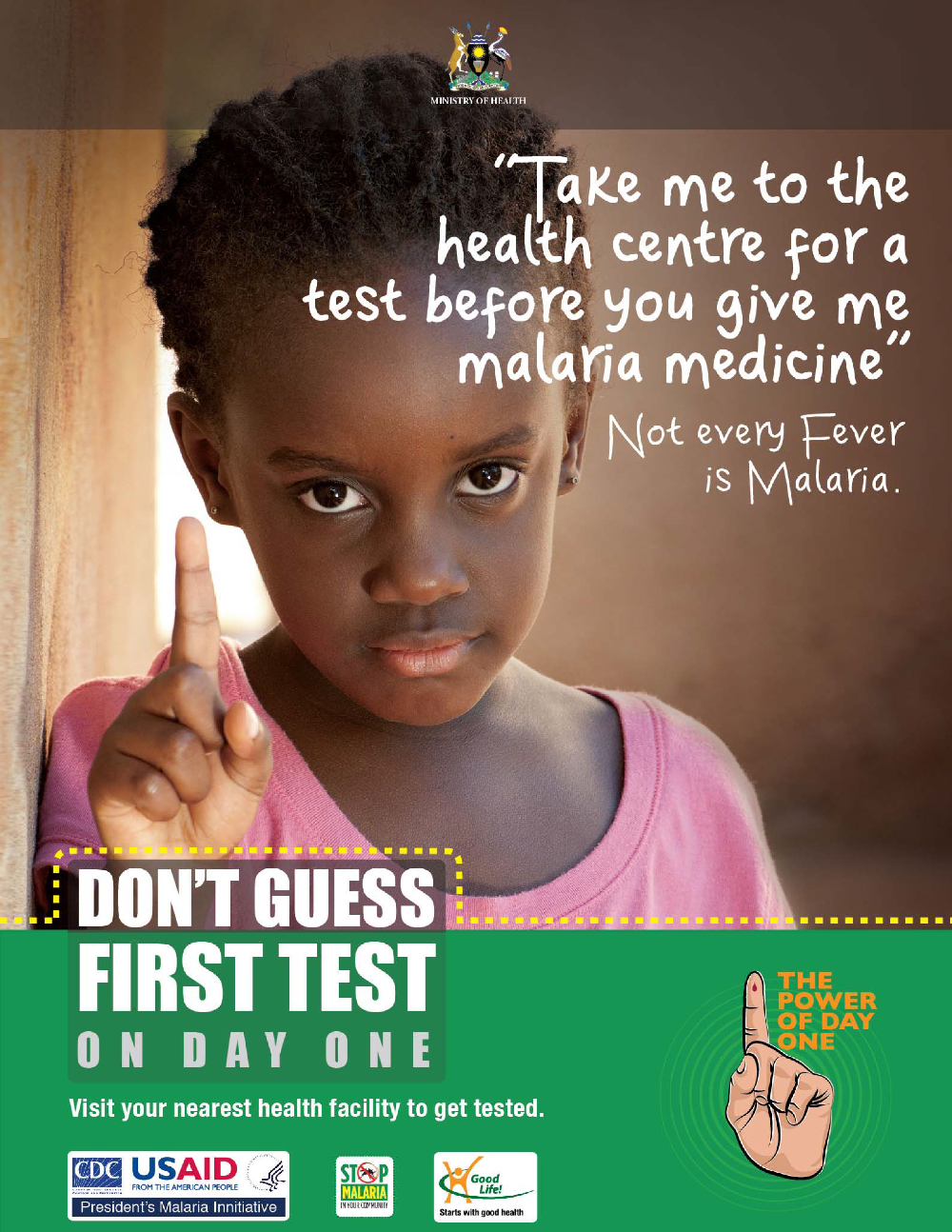

The campaign targeted caregivers of children under 5 and clinical public health workers with the slogan, “Don’t Guess, First Test,” which promoted two behaviors: 1) all individuals exhibiting symptoms of malaria should get a malaria test, and 2) only those who test positive for malaria should receive treatment for malaria. Individuals who receive a negative test result for malaria should try to identify and treat the actual source of their symptoms.

Activities carried out during this campaign included:

- Mass media – Posters, billboards and radio spots to reach a large proportion of the intended audiences.

- Training and support supervision – Health providers were trained to improve their skills in managing fevers and communicating with caregivers about the importance of testing and adherence to test results. Training was reinforced by support supervision visits.

- Interpersonal communication – Group health education talks and one-on-one discussions between caregivers and Village Health Team members or other health providers gave caregivers more opportunities to learn about and discuss the new recommendations.

The Test and Treat campaign built on an existing campaign that promoted testing in Uganda. The “Power of Day One” campaign, implemented by the AFFORD Project for a year before this campaign, promoted testing and treatment for malaria within 24 hours of fever onset. The Power of Day One campaign contributed to increased uptake of ACT and rapid diagnostic testing in private sector health facilities, pharmacies and drug shops in four districts, which were part of the 24 districts covered by SMP.

- The Ministry of Health’s National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) provided overall direction for the campaign. In addition to advising the partners on the Ministry’s strategic areas of interest, the NMCP helped ensure that diagnostic commodities were available to public health facilities in the participating districts. District health officials were positioned as master trainers to train clinical staff in their regions and provide supportive supervision in the rollout of the new protocol.

- As the lead implementing partner for SMP, CCP provided technical leadership for the design, implementation and M&E of the communication strategy

- Malaria Consortium (an SMP partner) designed and conducted provider training, developed training materials (intermittent parasite clearance [IPC] guides for national and district trainers), provider workbooks, a checklist for diagnosis of fever among children under 5 and a continuing medical education guide. Malaria Consortium also participated in support supervisory visits to participating health facilities.

- Mango Tree developed a flipchart for providers to use during patient counseling.

- Uganda Health Marketing Group and their contracted advertising agencies led the design, production and placement of media materials, including posters, billboards and radio spots. Pretesting was done in collaboration with SMP and NMCP. Uganda Health Marketing Group also led training of private-sector providers in diagnostic capacity, and led rollout of the campaign in private-sector facilities in six districts.

- World Vision integrated the Test and Treat messages in its distance radio learning program for village health teams, which are made up of community volunteers who provide basic health education and referrals for services.

Results

The combination of a designated coordinator, clear guidelines, access to tests and ACTs, the promotion of testing and appropriate treatment to providers and caregivers, and efforts to increase providers’ ability to manage febrile cases and communicate effectively with caregivers all contributed to the campaign’s success.

The evaluation of the campaign found a demonstrated a shift in provider practices. Providers with any exposure to the campaign were more likely to test all children who reported with fever (91-97 percent vs. 81 percent) and were less reliant on clinical diagnosis. Providers who were trained and exposed to the media campaign were more likely to conduct a differential diagnosis (86 percent vs. 76 percent) and less likely to prescribe antimalarial drugs for children with fever who tested negative for malaria (15–25 percent vs. 37 percent). Finally, providers who received clinical training that included IPC and counseling skills were more likely to tell caregivers that antimalarial treatment was not necessary after a negative test result (80 percent vs. 50 percent) and more likely to provide alternative diagnosis (86 percent vs. 76 percent). The campaign also improved availability and stocking of malaria drugs. Because service providers only treat when test results are positive, drugs are available for people who actually have malaria.

Application

Coordination is crucial when introducing new technology or services that require a shift in provider and client behavior. As the national governing bodies, the Ministry of Health is the appropriate body to establish protocols and policies and to be responsible for training public health sector staff. Development partners can contribute by supporting training and education and generating demand through communication and social mobilization. Civil society’s role is often to mobilize communities and advocate for equity, accessibility and appropriateness of services.