Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative

Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative

This case study illustrates how the elements of service communication can be applied in a real-world situation, and how use of social and behavior change communication (SBCC) approaches can significantly improve access, uptake and quality of health services, in turn leading to better health outcomes. The Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) applied best practices in SBCC throughout the stages of service delivery to revitalize Nigeria’s family planning program in urban areas. The program sought to gain maximum insight about its intended audiences and developed an appealing branded campaign that shared the functional and emotional benefits of family planning. The project developed the skills of public and private sector providers to ensure that clients understood benefits of different contraceptive methods, and conducted mobile outreach to reduce barriers to access. The project also worked to create a supportive environment that encouraged households and communities to discuss family planning openly, enabling more individuals to explore the benefits of family planning, identify the best method for them and sustain its use over time.

NURHI is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and managed by Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP). The Association for Reproductive and Family Health and Centre for Communication Programs, Nigeria are key partners, along with collaborating organizations such as the African Radio Drama Association, the Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria, Advocacy Nigeria, Development Communications Network, the Futures Institute and Marie Stopes International Nigeria. The project was designed to assist the Nigerian government in revitalizing its family planning program and increase the contraceptive prevalence rate by 20 percentage points. NURHI focused its efforts on promoting contraceptive methods for birth spacing and limiting births, with a particular aim of increasing access to family planning among the urban poor. The first phase of the project ran from 2009 to 2014 in six urban centers: Abuja, Benin City, Ibadan, Ilorin, Kaduna and Zaria. NURHI originally had five objectives: A sixth objective was added in 2012: One in every six Africans is Nigerian. As the continent’s most populous country, Nigeria is also experiencing a “youth bulge,” with more than half of the population under 24 years old. This is due in part to the country’s high fertility. On average, a Nigerian woman has six children, placing the country’s birth rate at 12th highest in the world. Compounding this situation, Nigeria’s poverty and health statistics are among the worst in Africa. When NURHI began in 2009, the World Bank estimated that 83 million Nigerians (62 percent of the population) lived on less than $1.90 per day, and infant and maternal mortality rates were alarmingly high (85 deaths per 1,000 live births, and an adjusted maternal mortality ratio of 610 per 100,000 live births, as of 2010). There seem to be unique moments in time when individuals are particularly receptive to new information and motivated to make changes. NURHI’s Gateway Behaviors Study used formative research that identified two gateway behaviors – completing at least four antenatal care visits during pregnancy and interpersonal communication on family health matters – that influence other health behaviors, such as family planning, exclusive breastfeeding and immunization. Piloted in Ilorin South from September 2013 to December 2014, the study used SBCC and social mobilization to engage pregnant women, their partners and their mothers-in-law. The project created profiles for each intended audience and leveraged key life events, such as naming ceremonies and weddings, as gateway moments to promote antenatal care and communication about family health matters. Advocacy and provider training ensured services were welcoming and competent. Registration of pregnant women in the pilot area increased substantially as a result of these interventions.About NURHI

Challenge[1]

Gateway Behaviors Study

Nigeria is also increasingly urban. Estimates place some 48 percent of Nigerians in urban environments, with the rate of urbanization at just under 5 percent. There are at least 10 cities with more than 1 million residents, and 15 percent of the population lives in the country’s six largest cities. Poverty and slum conditions pose health threats to Nigeria’s fast-growing urban centers. More than 51 percent of urban dwellers live below the poverty line, and many lack adequate housing, sanitation, and waste management.

Despite a thriving family planning program in the 1980s and early 1990s, Nigeria suffered from changing donor priorities and funding. This contributed to stagnating trends in fertility, contraceptive use, and method mix over the past 10 years. In 2009, with contraceptive prevalence at only 10 percent, a total fertility rate of 5.7, and unmet need at 20 percent, there was a pressing need to reinvigorate family planning efforts at national, state, and city levels. Meanwhile, policies and programs remained mostly on paper. There were a few national working groups focused on policy implementation, but family planning received little attention at state and local levels. Consequently, the family planning program was largely funded by external donors, the health system paid little attention to family planning, and many journalists and local leaders were vocally opposed to family planning. Unsurprisingly, government health facilities were poorly staffed, minimally equipped, and riddled with contraceptive stock-outs. Many couples obtained family planning services from proprietary and patent medicine vendors (PPMV), who can only dispense condoms and refill oral contraceptives to current users or pharmacists. Access to implants and IUDs were restricted to a few hospitals.

Response

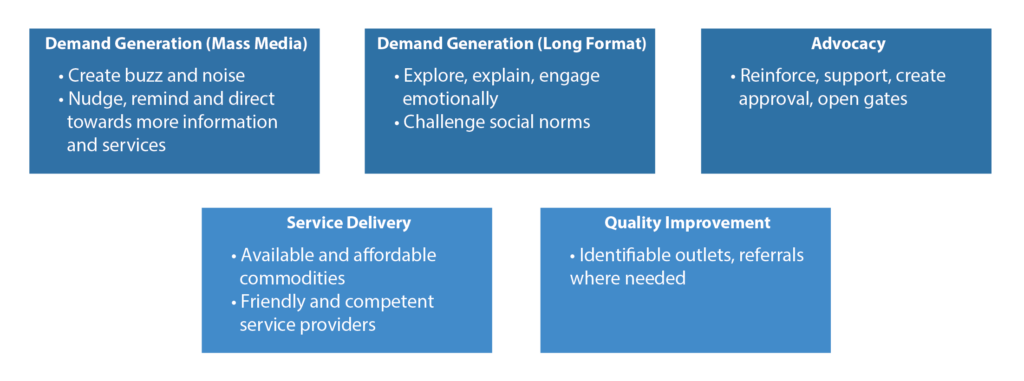

NURHI’s SBCC approaches were employed throughout the three stages of service delivery, with specific roles in each stage:

- Before services were delivered by raising general awareness about family planning and available services, addressing community and social norms, and reviving demand for family planning

- During services by ensuring that all service providers (clinical and non-clinical, private and public sector) were able to provide high-quality family planning counseling and services and increasing access through mobile outreach

- After services by promoting open discussion about family planning within couples and peer groups and soliciting the support of community leaders and local government to sustain commitment to family planning efforts

NURHI’s approach to improving access to and quality of family planning services led with demand generation efforts that applied a “consumer lens” to communicate about and deliver services. The hypothesis was that creating demand would, in turn, drive supply, thereby creating a sustainable response. As the graphic below illustrates, the project’s approaches to demand generation and service delivery mutually reinforced one another.

NURHI systematically used research, consumer feedback (through pre-testing) and monitoring data to revise and refine its messages.

[1] Statistics in this section are from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2212.html and http://datatopics.worldbank.org/hnp/HNPDash.aspx

Bringing Clients to Services

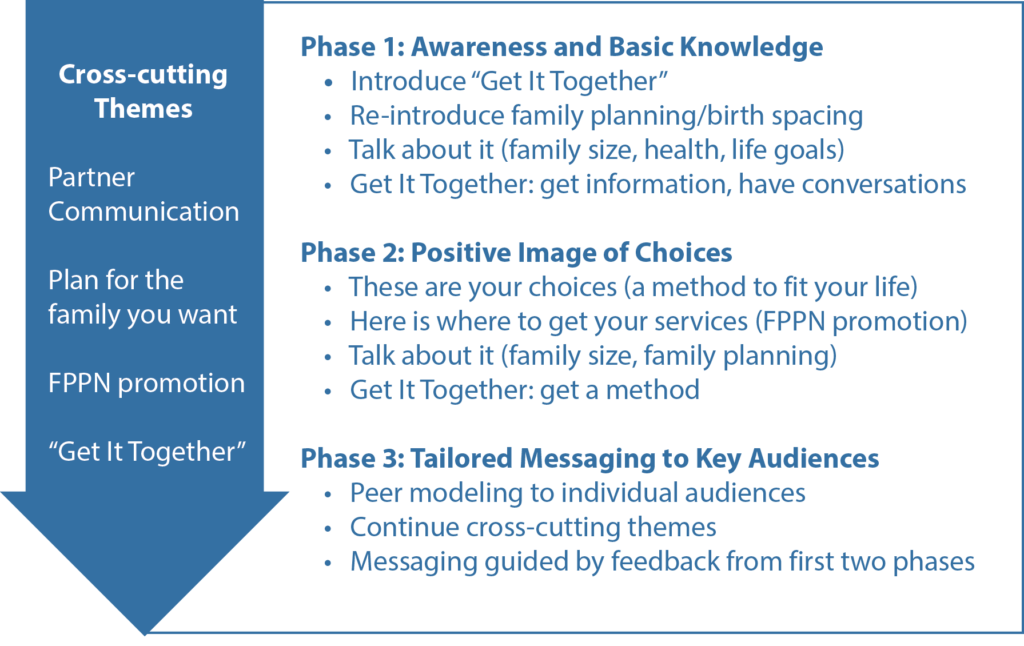

To create interest and demand for family planning services, NURHI used the situation analysis and audience insight to design a multi-phased, multi-channel demand generation strategy built around a highly visible umbrella brand, “Get It Together.” For more information on how to develop a brand, see How-To Create a Brand Strategy Part 2.

Step 1: Segmenting, Prioritizing, and Profiling the Intended Audience

In assessing the family planning situation, NURHI used qualitative and quantitative research, including focus group discussions, a Baseline Household Survey, secondary analysis of the 2008 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey and a social mapping exercise to learn about community members’ attitudes toward family planning services and identify points of entry for social mobilization activities. NURHI used the concept of ideation to identify beliefs, emotions and behaviors that contributed to individual family planning use and worked to influence those factors.

In 2010, NURHI held a participatory design workshop to analyze research findings and draft the demand generation strategy.

In 2010, NURHI held a participatory design workshop to analyze research findings and draft the demand generation strategy.

Step 2: Draft a Demand Generation Strategy

The demand strategy linked closely with NURHI service delivery, advocacy and public-private partnership activities. In its branded media campaign (see below), NURHI used a variety of mass media channels, community-level activities and referrals for family planning services led by social mobilizers, and an “entertainment-education” radio drama featuring satisfied users who modeled family planning use and promoted services.

Step 3: Design and Test Materials and Interventions

Branding: NURHI worked with an advertising agency to develop a campaign brand and materials based on audience insights. A creative brief guided the agency to develop a campaign targeting 15- to 45-year-old women and 20- to 50-year-old men living in slums. The brand logo, finalized after pre-testing, included a tagline (“Know. Talk. Go.”) that encouraged the target audience to know about family planning, talk with partners about family planning, and go for family planning services. NURHI also worked with the agency to produce a package of branded radio and television spots and print materials.

Community mobilization: NURHI and partner Centre for Communication Programs, Nigeria designed a social mobilization strategy that engages young (18- to 35-year-old) barbers, tailors, hairdressers and motorcycle delivery people to discuss family planning with individuals and groups.

Entertainment-education: NURHI and partner African Radio Drama Association produced three seasons of a weekly radio program in each target city. See a step-by-step narrative of the radio design process.

The illustration below depicts how the campaign rolled out messages in three phases. The first phase built awareness and introduced the topic of family planning among targeted communities; the second phase introduced the range of modern contraceptive options to motivate informed choice; and the third phase encouraged behavior change through tailored messages for specific audience segments.

Reaching Urban Youth

The Urban Adolescent SBCC Implementation Kit (I-Kit) provides a selection of essential elements and tools to guide the creation or strengthening of sexual and reproductive health SBCC programs for urban adolescents aged 10 to 19. The I-Kit is designed to teach these essential SBCC elements and includes worksheets to illustrate each element and facilitate practical application.

Step 4: Campaign Launch

NURHI launched Get It Together in four cities in October 2011, with television and radio spots and posters in high-traffic areas. Service providers received branded job aids, print materials, and promotional items. Social mobilizers also received branded promotional and educational materials. Trained mobilizers facilitated radio listening groups, conducted visibility parades, leveraged key life events for points of discussion, spearheaded neighborhood campaigns and referred clients to Family Planning Providers Network (FPPN) services with Go Referral Cards. After six months of the campaign, radio programs began weekly broadcasts. Each program included a serial drama episode, interviews, music, and a weekly quiz, plus a live call-in session with a family planning expert. Listeners could win prizes by answering weekly questions through text messaging.

Client-Provider Challenges

NURHI’s service delivery strategy focused on facilities with high-volume services – defined as public or private health facilities with the highest volumes of antenatal, delivery, family planning and immunization clients. Most were tertiary or teaching hospitals, secondary facilities or general hospitals, military hospitals, and hospitals that provide free maternity services. Research showed that pharmacies and PPMVs were additional points of access for family planning services and information, so NURHI developed criteria to select pharmacies and PPMVs, including their willingness to join the FPPN.

NURHI adopted three approaches to address the challenges of service delivery.

- Improving the quality and accessibility of services: NURHI provided robust training for service providers in family planning counseling and IUD and implant insertion and services. The project also worked at facility level to improve contraceptive logistics and management systems. Training included in-person, on-site clinical training, on-the-job training for counseling, distance learning via mobile platforms, and supportive supervisory visits. NURHI used mobile teams of service providers from Marie Stopes International Nigeria to reach additional clients. NURHI also helped upgrade services with additional equipment, using a “clinic makeover” approach to rapidly make each site more inviting and pleasant for clients.

- Integrating family planning with existing maternal, neonatal, and child health and HIV services: NURHI developed an integration strategy , provided onsite training for high-volume service providers in family planning counseling and strongly promoted postpartum IUD services. Because these services were already at capacity, NURHI created an active referral program to route clients to dedicated FP services.

- Strengthening relationships and referrals between public and private sector family planning providers: NURHI enhanced referrals systems to ensure that clients who need family planning services have access to them. Social mobilizers received branded Go cards [insert image] to refer community members to high-volume services sites and allow service providers to know who referred the client, gave mobilizers the ability to follow up with clients and enabled the project to collect data for analysis. NURHI also used existing referral mechanisms to track clients when they were sent to a different facility within the network. The referral strategy articulated roles and responsibilities among service providers, facility management, community mobilizers, NGOs and NURHI staff.

Engaging Private Providers

NURHI created the FPPN to establish a platform where family planning providers could interact and work together to increase access, referrals, and family planning service quality. This public-private initiative supported clinical and non-clinical service providers to improve contraceptive logistics management, increase the quality of family planning service delivery through training, strengthen referrals between service delivery points, and use branding and promotion to increase access to and uptake of family planning services. In 2014, the FFPN became the Sustainable Family Planning Providers Association and developed a strategic plan, through 2018, with goals to increase utilization, expand and sustain the family planning method mix, improve service quality, and win support from local leaders.

Maintaining Behavior

NURHI’s advocacy strategy focused at the state and local levels to engage local government officials, community leaders and the media to support family planning efforts. Partners with expertise in local advocacy assisted the project in needs assessment and identified stakeholders to participate in advocacy efforts. NURHI’s Advocacy Core Groups assembled leaders from each city to identify high-priority policy issues and develop advocacy plans to address them. NURHI facilitated the creation of national and site-specific advocacy kits with position papers, policy briefs and fact sheets to support local advocacy efforts.

Futures Institute created tools to stimulate dialogue on the impact of population on the environment, social services and economic development. Advocates were trained to use a number of advocacy tools (Spitfire training materials, budget projections and tracking) to push local governments to prioritize family planning in development plans and budgets. NURHI also targeted media outlets using its media advocacy strategy to enhance the quality and quantity of media coverage of maternal and child health issues, with a focus on family planning.

NURHI identified and engaged community leaders and community groups to increase their support of and involvement with family planning, providing them with messages and strategies to address health concerns and the fear of side effects. The project also formed interfaith forums in each city to bring together religious leaders once a year to collaboratively develop messages and strategies to increase family planning use in their communities.

Service communication and behavioral maintenance was further supported through the Get It Together campaign’s focus on dispelling myths and promoting open discussion about family planning among couples and peer groups, making the use of family planning more acceptable and desirable.

Coordination

A complex array of partners contributed to NURHI’s success, working under varied partnership models—formal partnerships, contracting and procurement, creation of new platforms and leveraging of existing structures. These partnerships allowed NURHI to expand the scope and scale of its activities. Clear roles and responsibilities in planning, implementation, and M&E ensured that all partners understood expectations about their contributions to the project. NURHI supported national, state, and local government structures to set the strategic direction of activities and monitor progress toward goals. The FPPN provided a platform to engage the service providers, particularly those in the private sector.

NURHI employed an advocacy and behavior change officer to monitor and coordinate the mass media radio program and social mobilization activities through regular meetings with partners, radio program monitoring, and tracking referrals by social mobilizers for family planning services.

Results

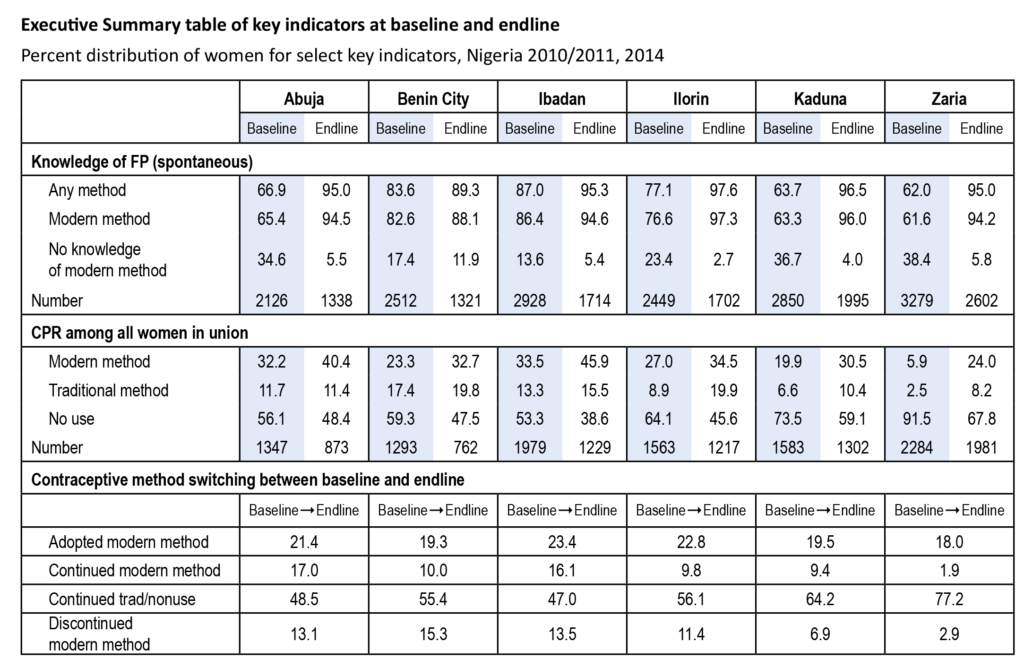

NURHI showed immediate results and continuous progress. The midterm assessment survey conducted after one year of implementation showed that 83 percent of men and women knew about the NURHI ‘Get it Together’ campaign. The NURHI midterm survey results showed an increase of 3–15 percent in contraceptive prevalence rates in the four initial cities in less than two years. The data also revealed that the proportion of women who intend to use family planning increased from 7.5–10.2 percent.

The 2013 National Demographic Health Survey showed an increase in family planning contraceptive prevalence rate in cities where NURHI operated.

Endline results showed significant increases in knowledge about family planning and increased contraceptive prevalence rates in every city where NURHI intervened, with significant increases in use of modern methods. These results demonstrate that the project was able to communicate effectively about family planning and motivate women to use modern methods.

Other results include establishing the FPPN as the Sustainable Family Planning Provider Association and increased budgetary support for family planning from state and local governments. Media reporting is now more pro-family planning, and national leaders are more vocally supportive of family planning. NURHI’s channel analysis determined that radio and community mobilization activities were the best investments, in terms of cost effectiveness.

Next Steps

Phase II of the NURHI project commenced in October 2015. This five-year phase is being implemented at the state level in Lagos, Kaduna and Oyo. NURHI II continues to use the premise proven under NURHI I: that demand for family planning is a requirement for increased contraceptive use and that will lead to increased contraceptive supply and available services

Additional Resources

NURHI project website: www.nurhitoolkit.org

Measurement, Learning & Evaluation Project, Urban Reproductive Health Initiative: https://www.urbanreproductivehealth.org/projects/nigeria