Components

Approaches to Integrated SBCC

While the theory helps you explain why and how your program should work, the approach provides an overarching method for carrying out your integrated program. The field of integrated SBCC is evolving and new approaches are continually emerging. Below are some approaches that have been implemented successfully.

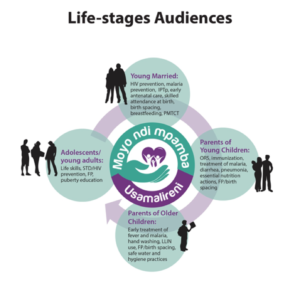

Approach: Life Stages Approach

In the Life Stages Approach, programs reach audiences (see Figure 6, below) with information and skills that are relevant to their stage in life, in the belief that providing audiences with information they need when they need it increases the likelihood of its use. The Life Stage approach segments the family and society as a whole according to the age- or stage-appropriate needs of each member, addressing the household as a key decision-making unit. This approach acknowledges that each life stage, while transitional, has its own specific behavioral objectives and health needs. Promoting positive health behavior at early stages represents a positive health investment and will have a cumulative, sustainable impact on future health behavior.

Program Experience

(When you see a Program Experience, simply click on the photo to read insights from real integrated SBCC programs.)

Approach: Gateway Behavior or Moment Approach

In the Gateway Behavior or Moment Approach, “Gateway” refers to a positive health behavior or to a facilitating factor that may trigger or facilitate other positive health behaviors, both simultaneously and across the family life cycle. For example, getting women to attend ANC can then lead to IPTp uptake, HIV testing, birth planning and other healthy behaviors.

Program Experience

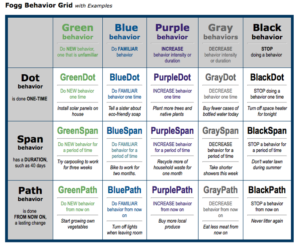

Approach: Behavioral Attributes Approach

The behavioral attributes approach takes into account that behaviors from different health or development topics may have more in common than behaviors from the same health area. For example, messaging about daily adherence to both antiretrovirals (ARVs) (HIV) and oral contraceptive pills (family planning) might be more similar than messages about ARV adherence and CD4 testing, which are both part of an HIV program.

To determine which behaviors might be promoted together, examine their attributes (i.e., the characteristics that define the behavior). Analyze the similarities and differences across the health areas and behaviors in your intended program to determine if there are ways to combine and package content that will improve impact, economies of scale, cost-effectiveness or program efficiency. Consider these potential points of convergence or divergence when determining which health areas and/or behaviors to package together.

Points to Consider:

- What is the frequency of the behaviors you are looking to influence – daily, weekly, monthly or yearly? Are they one-time behaviors (e.g., voluntary medical male circumcision), behaviors enacted for a certain period of time (e.g., exclusive breastfeeding for six months) or practices the audience is familiar with? Are the behaviors habitual, or do they require a deliberative process? Are you aiming to increase the behaviors (e.g., exercise), decrease the behaviors (e.g., reduce sugar consumption) or stop a behavior completely (e.g., smoking)? What time of the day do the behaviors happen (e.g., morning, evening or at multiple time points)?

- What are the financial, logistical and social costs of the behaviors? Are they costly? Cheap? Free? How easy or complicated are the behaviors? Are they stigmatizing or pride-inducing?

- Do similar structural (e.g., distance to the health facility, infrastructure, law or policy) or ideational (e.g., attitudes, couple communication, self-efficacy or social ties) factors affect the behavior?

- Are the behaviors done publicly or in private? Do the behaviors require the agreement or support of others, or can they be done alone? Are there any concerns around anonymity (e.g., HIV testing and counseling)?

- Are the behaviors shaped by gender norms, inequality or other social factors? Is the behavior of high cultural significance (e.g., traditional male circumcision)?

- If behaviors require interaction with a health provider, what needs to happen before, during and after the client-provider interaction (e.g., demand creation, quality counseling and adherence, respectively)?

These behavioral attributes can affect messaging, timing, phasing, channel selection and other parts of the strategy (Source: Rajiv Rimal, “Social and Behavior Change Communication at the Crossroads (and Crosshairs): What’s Next?” Plenary Presentation at the International SBCC Summit 2016: Elevating the Science and Art of SBCC, Addis Ethiopia, February 2016).

Program Experience

Approach: Co-occuring Behaviors

Some integrated SBCC efforts focus on targeting behaviors that tend to occur together. Common examples include HIV and TB prevention and control, and HIV and substance abuse prevention. SBCC efforts often seek to address common drivers of co-existing behaviors, use entry points accessed for one issue to address the other issue(s) and link the issues/behaviors in the minds of the audiences.

Approach: Progressive Integration Approach

Often, programs seek to broaden a behavior change effort by adding new health areas onto an existing health program. This allows the program to take advantage of existing buy-in, structures and platforms. Examples include integrating family planning into immunization and other child health programs, integrating HIV into family planning or vice versa, and integrating maternal and child nutrition into child health programs.

These approaches are in no way mutually exclusive. An integrated program may use some or all of these approaches – for example, brand the campaign under one common umbrella, use a life stage approach, employ gateway behaviors and adopt co-existing or progressive integration. The integration approach(es) selected will impact many decisions about project design.