Program Experiences

Program Experience: Advantages of Integrated SBCC

Through its network of facilities, the Malawi Ministry of Health provides a range of essential healthcare package (EHP) services under one roof to catchment populations. USAID’s three Support for Service Delivery Integration (SSD-I) initiatives – SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems – supported the Ministry of Health to deliver a wide range of EHP interventions in an integrated manner to increase access, quality and utilization. All individuals interviewed by the evaluation team valued the SSD-I initiatives’ assistance with the integrated service delivery model.

Through its network of facilities, the Malawi Ministry of Health provides a range of essential healthcare package (EHP) services under one roof to catchment populations. USAID’s three Support for Service Delivery Integration (SSD-I) initiatives – SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems – supported the Ministry of Health to deliver a wide range of EHP interventions in an integrated manner to increase access, quality and utilization. All individuals interviewed by the evaluation team valued the SSD-I initiatives’ assistance with the integrated service delivery model.“From a management point of view, [integration] increases efficiencies. From the service providers’ perspective, it is empowering. From the clients’ perspective, the model provides the opportunity to receive coordinated care rather than having separate visits for separate services”– Senlet, Kachiza, Katekaine, & Peters, 2014

Program Experience: What is a Coordinating Body?

The Communication for Health Communities (CHC) project in Uganda coordinated national-level processes through the national Behavior Change Communication Working Group, which was led by the MOH with representation from implementing partners. It coordinated district and community-level activities through seven regional offices located in central Kampala, South Western, Eastern, Northern, Western, West Nile and Karamoja.

Program Experience: How to Establish a Coordinating Body

The Management Advisory Group (MAG) served as the coordinating body for the three SSDI projects in Malawi – SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems. Initially, the MAG was comprised of the senior and technical project staff of the three activities and was chaired by the SSDI-Services Chief of Party (COP) with the objective of strengthening coordination amongst the three activities. Once implementation began, the composition of the MAG was expanded to include the USAID Health Office, including the Agreement Officer’s Representatives (AORs) and all technical staff. The MAG was instrumental in providing guidance as a management body.

The Management Advisory Group (MAG) served as the coordinating body for the three SSDI projects in Malawi – SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems. Initially, the MAG was comprised of the senior and technical project staff of the three activities and was chaired by the SSDI-Services Chief of Party (COP) with the objective of strengthening coordination amongst the three activities. Once implementation began, the composition of the MAG was expanded to include the USAID Health Office, including the Agreement Officer’s Representatives (AORs) and all technical staff. The MAG was instrumental in providing guidance as a management body.

Program Experience: Sample Vision Statement

Health Communication Component (HCC) envisions a Pakistan where individuals, families and communities advocate for their own health, practice positive health behaviors (e.g., timely use of maternal, newborn and child health [MNCH] and family planning/reproductive health services) and engage with a responsive health care system (HCC, 2015).

Health Communication Component (HCC) envisions a Pakistan where individuals, families and communities advocate for their own health, practice positive health behaviors (e.g., timely use of maternal, newborn and child health [MNCH] and family planning/reproductive health services) and engage with a responsive health care system (HCC, 2015).

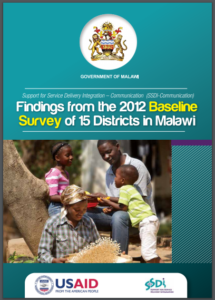

Program Experience: Three Projects, One Shared Vision

Through the USAID SSDI initiative in Malawi, activities were awarded and implemented through three separate Cooperative Agreements: SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems. All three SSDI projects targeted the same 15 districts and were expected to collaborate and work together throughout the life of the project. Each implementing partner had a distinct scope of work and mandate, but one shared vision. The goal of all three Cooperative Agreements was to contribute to progress in three critical areas:

Through the USAID SSDI initiative in Malawi, activities were awarded and implemented through three separate Cooperative Agreements: SSDI-Services, SSDI-Communication and SSDI-Systems. All three SSDI projects targeted the same 15 districts and were expected to collaborate and work together throughout the life of the project. Each implementing partner had a distinct scope of work and mandate, but one shared vision. The goal of all three Cooperative Agreements was to contribute to progress in three critical areas:

- Reduce fertility and population growth, which are essential for attaining broad-based economic growth;

- lower the risk of HIV/AIDS to mitigate the enormous impact on human resources and productivity; and

- lower maternal and infant and under-five mortality rates.

Aware of the fact that they all had the same end goal, the projects did their best to collaborate and coordinate among themselves to maximize impact.

(Adapted from the USAID/Malawi Support for Service Delivery – Integration Performance Evaluation by Pinar Senlet, Chifundo Kachiza, Jennifer Katekaine and Jennifer Peters [2014].)

Program Experience: Donor and Government Leadership Role

Donors and government have key roles to play in advocacy, coordination and expectation setting with partners and within their own institutions. These leadership structures are often best placed to facilitate integration. It is usually much more effective to have the call for coordination come from the government and the funding agency than an implementing partner. In Guatemala, for example, the USAID Feed the Future portfolio was integrated across health, nutrition, education, economic growth, food security and climate change. More than 12 projects funded by USAID were given a similar goal: to contribute to the reduction in chronic malnutrition. With a huge need to integrate messaging, USAID invited HC3 to harmonize the many messages cutting across the different projects, partners and sectors, and made explicit to partners their desire for communication to support this integration effort. With this expectation set and reinforced by USAID, partners were better able to see the advantages of message harmonization and close collaboration to increase the impact of their work.

Donors and government have key roles to play in advocacy, coordination and expectation setting with partners and within their own institutions. These leadership structures are often best placed to facilitate integration. It is usually much more effective to have the call for coordination come from the government and the funding agency than an implementing partner. In Guatemala, for example, the USAID Feed the Future portfolio was integrated across health, nutrition, education, economic growth, food security and climate change. More than 12 projects funded by USAID were given a similar goal: to contribute to the reduction in chronic malnutrition. With a huge need to integrate messaging, USAID invited HC3 to harmonize the many messages cutting across the different projects, partners and sectors, and made explicit to partners their desire for communication to support this integration effort. With this expectation set and reinforced by USAID, partners were better able to see the advantages of message harmonization and close collaboration to increase the impact of their work.

Program Experience: National Strategies Guide Design

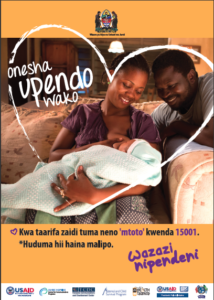

Several national strategies and guidelines were instrumental in guiding the strategic design of Tanzania’s Wazazi Nipendeni campaign, which integrated MCH, PMTCT, malaria prevention, family planning and nutrition into an overarching safe motherhood campaign. Most notably, the campaign aimed to operationalize the Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa in Tanzania (CARMMA/Tz) and the National Road Map Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal, Newborn and Child Deaths in Tanzania 2010-2015 (One Plan).

Program Experience: Collaborative Design

Where partners have communication staff, an SBCC working group to develop and collaborate on implementing the integrated SBCC strategy can further increase buy-in and build SBCC capacity. In Guatemala, for example, HC3 organized meetings, workshops and consultations with communication staff of the Western Highlands Integrated Program (WHIP) implementing partners. Workshops were used to share a message consistency analysis and situation analysis, build capacity for formative research and use of data for decision-making, develop the integrated SBCC strategy and develop a radio campaign, among other things.

Where partners have communication staff, an SBCC working group to develop and collaborate on implementing the integrated SBCC strategy can further increase buy-in and build SBCC capacity. In Guatemala, for example, HC3 organized meetings, workshops and consultations with communication staff of the Western Highlands Integrated Program (WHIP) implementing partners. Workshops were used to share a message consistency analysis and situation analysis, build capacity for formative research and use of data for decision-making, develop the integrated SBCC strategy and develop a radio campaign, among other things.

Program Experience: Formative Research Methodologies

In a recent interview, Fayyaz Khan shared that SSDI used FGDs, IDIs, a mapping process and extensive visuals in their formative research process. They designed the research to address questions such as:

In a recent interview, Fayyaz Khan shared that SSDI used FGDs, IDIs, a mapping process and extensive visuals in their formative research process. They designed the research to address questions such as:

What do people value?

How do they perceive health?

Is HIV more dangerous than malaria or not?

How do they perceive the value of losing a child?

What is the value of a woman?

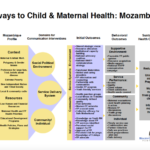

Program Experience: Socio-Ecological Model

Example: In Guatemala, the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) developed a Social Ecological Model (SEM) (figure X, below) for unifying and promoting integration between Western Highlands Integrated Program (WHIP) projects working in the areas of health, nutrition, hygiene, agriculture, food production, and water use sectors, with the aim of strengthening the effectiveness and impact of the programs with more citizen participation and involvement of the indigenous population, thereby promoting sustainable development. USAID initiated the WHIP project to bring together multiple projects and implementing partners to address multi-sectoral goals related to reduction of malnutrition and poverty, improvement of economic growth, local governance and social development, and the sustainable management of natural resources to mitigate the impact of climate change.

Example: In Guatemala, the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) developed a Social Ecological Model (SEM) (figure X, below) for unifying and promoting integration between Western Highlands Integrated Program (WHIP) projects working in the areas of health, nutrition, hygiene, agriculture, food production, and water use sectors, with the aim of strengthening the effectiveness and impact of the programs with more citizen participation and involvement of the indigenous population, thereby promoting sustainable development. USAID initiated the WHIP project to bring together multiple projects and implementing partners to address multi-sectoral goals related to reduction of malnutrition and poverty, improvement of economic growth, local governance and social development, and the sustainable management of natural resources to mitigate the impact of climate change.

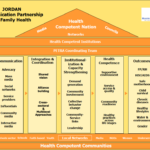

Program Experience: Health Competence

Example: The Jordan Health Communication Partnership used a Health Competence framework to guide its integrated programming.

Program Experience: Bounded Normative Influence

Example: In Mozambique, Tchova Tchova Historias de Vida (TTHV) used BNI for its design and evaluation, with couples and communities as its bounded subgroups. TTHV used real story videos to engage community members and couples in an open discussion and debate about sexual and gender norms. Through organized community group discussions, married couples were invited to participate in nine sessions that addressed a variety of issues related to HIV risk behaviors. While the project focused on HIV, the application of BNI in Tchova Tchova may have wider significance for integrated projects.

Program Experience: Communication for Social Change (C4SC)

Example: Ghana’s Behavior Change Support (BCS) project employed a C4SC model to blend community, interpersonal and mass media approaches across all of its health areas to integrate its four program elements: behavior change communication; community mobilization; systems strengthening; and capacity building. As part of its strategy development process, BCS fostered partnerships among key stakeholders, including the Ghana Health Service/Family Health Division, USAID, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and key program implementers.

Example: Ghana’s Behavior Change Support (BCS) project employed a C4SC model to blend community, interpersonal and mass media approaches across all of its health areas to integrate its four program elements: behavior change communication; community mobilization; systems strengthening; and capacity building. As part of its strategy development process, BCS fostered partnerships among key stakeholders, including the Ghana Health Service/Family Health Division, USAID, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and key program implementers.

Program Experience: Diffusion of Innovations (DOI)

Example: During the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, DOI helped encourage rapid behavior change. By training and equipping community volunteers and local leaders who were well respected, the HC3 team was able to quickly spread or “diffuse” correct information and positive health behaviors like safe burials throughout the community. These local leaders served as thought leaders and early adopters in their communities who then spread these new ideas to community members. Ebola messages were integrated with sanitation, hygiene and infection control messages that had already been promoted in Total Sanitation communities and among child survival programs.

Example: During the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, DOI helped encourage rapid behavior change. By training and equipping community volunteers and local leaders who were well respected, the HC3 team was able to quickly spread or “diffuse” correct information and positive health behaviors like safe burials throughout the community. These local leaders served as thought leaders and early adopters in their communities who then spread these new ideas to community members. Ebola messages were integrated with sanitation, hygiene and infection control messages that had already been promoted in Total Sanitation communities and among child survival programs.

Program Experience: Customized Theory

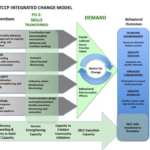

Example: One example of this is the TCCP Integrated Change Model. Central to the model was the belief that creating desire for change across all levels of society is at the heart of real progress. Multi-level communication strategies and interventions operated at the policy, community, family and individual levels. The model posited that, together, the interventions would catalyze demand by shifting perceptions of risk and efficacy at the individual behavioral level and norms and priorities at the socio-political and cultural levels.

Example: One example of this is the TCCP Integrated Change Model. Central to the model was the belief that creating desire for change across all levels of society is at the heart of real progress. Multi-level communication strategies and interventions operated at the policy, community, family and individual levels. The model posited that, together, the interventions would catalyze demand by shifting perceptions of risk and efficacy at the individual behavioral level and norms and priorities at the socio-political and cultural levels.

Program Experience: Life Stages Approach

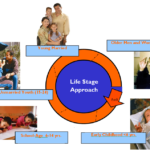

Examples: In Malawi, for example, SSDI developed their communication strategy around four key life stages: young married couples, parents with children under five, parents with older children and adolescents. The four life stages were adopted by all three SSDI projects–SSDI-Communication, SSDI-Services and SSDI-Systems (Source: HC3, 2016).

Examples: In Malawi, for example, SSDI developed their communication strategy around four key life stages: young married couples, parents with children under five, parents with older children and adolescents. The four life stages were adopted by all three SSDI projects–SSDI-Communication, SSDI-Services and SSDI-Systems (Source: HC3, 2016).

Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) in Egypt also used a Life Stages approach to address family members from birth through old age, with a special focus on newly married and young couples. CHL aimed to address a wide range of health areas using the Life Stages approach,  including family planning, reproductive health, MCH, infectious diseases (including HIV) and healthy lifestyles and practices.

including family planning, reproductive health, MCH, infectious diseases (including HIV) and healthy lifestyles and practices.

Communication for Healthy Communities (CHC) in Uganda was based on the Life Cycle/Life Stage approach. Due to its personal touch, the approach triggered rapport, honest dialogue and self-reflection and provided knowledge, motivation and skills on HIV prevention, HIV care and treatment, MCH, nutrition, family planning, malaria and TB. The interventions were aimed at shifting gender and social norms and providing supportive environments for adopting recommended heath actions/behaviors. They were implemented through targeted interpersonal communication (IPC), community mobilization interventions, mass media and social media as well as print and outdoor media.

Program Experience: Gateway Behavior or Moment Approach

Examples: In Bangladesh, Alive and Thrive has worked to integrated maternal nutrition into a large-scale MNCH program with the idea that maternal nutrition is a gateway to positive infant and young child feeding outcomes.

Examples: In Bangladesh, Alive and Thrive has worked to integrated maternal nutrition into a large-scale MNCH program with the idea that maternal nutrition is a gateway to positive infant and young child feeding outcomes.

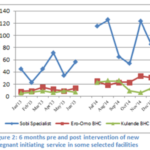

The Nigeria Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) used a gateway behavior approach to promote two key behaviors – completion of all recommended ANC visits and IPC on family health matters – with the hypothesis that adoption of these behaviors had significant potential to then facilitate the adoption of other health behaviors, including family planning, exclusive breastfeeding and  immunization.

immunization.

Program Experience: Behavioral Attributes Approach

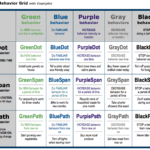

Example:  In Tanzania, the Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign used the Fogg Behavioral Model to inform its design. The Fogg model posits that there are three different durations of behaviors – one-time, over a limited period of time and indefinitely – and five different behavioral categories (a new/unfamiliar behavior, a familiar behavior, increasing behavior, decreasing behavior and ceasing behavior). This results in a grid of 15 possible types of behaviors (shown below). The design team mapped each of the campaign’s desired behaviors onto the grid in order to better understand their attributes, and, in turn, how to best address the target audience and trigger change (Source: Fogg, 2010).

In Tanzania, the Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign used the Fogg Behavioral Model to inform its design. The Fogg model posits that there are three different durations of behaviors – one-time, over a limited period of time and indefinitely – and five different behavioral categories (a new/unfamiliar behavior, a familiar behavior, increasing behavior, decreasing behavior and ceasing behavior). This results in a grid of 15 possible types of behaviors (shown below). The design team mapped each of the campaign’s desired behaviors onto the grid in order to better understand their attributes, and, in turn, how to best address the target audience and trigger change (Source: Fogg, 2010).

Program Experience: Target Audience

At the start of the Nuru integrated poverty reduction program in Kenya, the agriculture program targeted farmers, the financial inclusion program targeted entrepreneurs and the WASH, healthcare and education programs targeted the entire community. This caused Nuru to question how this assortment of programs focused in the same community was getting at people of extreme poverty faster, cheaper and more effectively than any one of the interventions alone. As a result, they changed their unit of impact to the farmer and their household, with all outcomes focused at aggregated up to that level (Changala, 2014).

Program Experience: Content and Messaging

In Uganda, the CHC project focused on engaging in dialogue with their audiences to determine content and messaging. Instead of the traditional, prescriptive health messages that tell audiences what to do, the project engaged people in a conversation, found out what was important to them and positioned relevant health actions in that context.

In Uganda, the CHC project focused on engaging in dialogue with their audiences to determine content and messaging. Instead of the traditional, prescriptive health messages that tell audiences what to do, the project engaged people in a conversation, found out what was important to them and positioned relevant health actions in that context.

Program Experience: Service Integration

As part of a Maternal and Child Health Integrated Project (MCHIP) program in Liberia, vaccinators asked mothers if they would also like to go for same-day, co-located family planning services to space their children (for rest and health) and mentioned that many other vaccinating mothers were doing it. This addressed the strong social stigma against resuming sex and using family planning before the baby walks (MCHIP, 2012).

As part of a Maternal and Child Health Integrated Project (MCHIP) program in Liberia, vaccinators asked mothers if they would also like to go for same-day, co-located family planning services to space their children (for rest and health) and mentioned that many other vaccinating mothers were doing it. This addressed the strong social stigma against resuming sex and using family planning before the baby walks (MCHIP, 2012).

Program Experience: A Flexible Creative Concept

Tanzania’s Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign initially covered the period from pregnancy to delivery. The campaign later extended to the first year of the child’s life in a second phase, and brought in a number of additional health issues, such as early and exclusive breastfeeding, immunization and post-partum family planning. The flexible and inclusive nature of the creative concept allowed for its expansion.

Tanzania’s Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign initially covered the period from pregnancy to delivery. The campaign later extended to the first year of the child’s life in a second phase, and brought in a number of additional health issues, such as early and exclusive breastfeeding, immunization and post-partum family planning. The flexible and inclusive nature of the creative concept allowed for its expansion.

Program Experience: Integrated SBCC Concepts and Life Stages

In Uganda, FHI360 developed the Obulamu (“How is life?”) umbrella campaign. The concept was flexible enough to adapt to different life stage audiences. For young couples, it turned into “How’s your love life?” For pregnant women and partners, “How’s your pregnancy?” For young families, “How’s Baby Opjo?” and for adolescent boys and girls, “What’s up?”

Program Experience: Mothers2Mothers

Task shifting (specifically around counseling) might be required to ensure enough time to effectively communicate multiple messages. In Malawi, for example, Mothers2Mothers (M2M) provides HIV education, support and referrals on TB, infant and maternal nutrition, cervical cancer and malaria, so the provider only needs to verify the clients’ understanding and needs. Additionally, group-based ANC has been a way to provide higher quality care to women in a more efficient manner.

Program Experience: Add-On

As a quick win in year one, SSDI-Communication agreed with another USAID-funded project, BRIDGE II, to co-fund the established Cheni Cheni Nchiti? (“What Is Reality?”) radio program, which previously focused only on HIV and AIDS. SSDI-Communication was able to take advantage of an existing platform with an existing audience ready for new content. The program was then repositioned to include other SSDI topics over time. Similarly, in Tanzania, the HIV-focused radio magazine programs initially started under the Strategic Radio Communication (STRADCOM) project were broadened under the TCCP follow-on to incorporate all of the integrated project’s health areas.

As a quick win in year one, SSDI-Communication agreed with another USAID-funded project, BRIDGE II, to co-fund the established Cheni Cheni Nchiti? (“What Is Reality?”) radio program, which previously focused only on HIV and AIDS. SSDI-Communication was able to take advantage of an existing platform with an existing audience ready for new content. The program was then repositioned to include other SSDI topics over time. Similarly, in Tanzania, the HIV-focused radio magazine programs initially started under the Strategic Radio Communication (STRADCOM) project were broadened under the TCCP follow-on to incorporate all of the integrated project’s health areas.

Program Experience: Umbrella Brand

Ghana’s Good Life initiative provides an excellent example of phasing using a teaser. The teaser segment lasted about three weeks and was designed to generate curiosity and mystery. It simply asked of the audience: What is your Good Life? What do you enjoy and value in life? Health topics were not introduced at this stage so as not to risk losing the interest of the audience. Six Ghanaians representing a cross-section of the country’s population were selected to tell personal stories about what they value in life and how health enabled them to achieve their good life. Their stories were produced for television, radio and print. See the full case study on how Ghana Good Life used umbrella branding.

Program Experience: Materials Distribution

The Government of Egypt (GOE) disseminated CHL materials through their network of more than 5,000 MOH clinics and 62 State Information Service-local Information Centers through fiscal year 2009. Thereafter, CHL provided selected printings upon the GOE’s special request, with approval from USAID. The print materials were distributed from the central level to the village Primary Health Care units (PHCs) following the MOH system of distributing commodities. The materials were also disseminated by NGO partners and the CHL private-sector program, including the AskConsult network of 30,000 pharmacies, AskConsult local gatherings, partner United Company of Pharmacies (UCP), trade magazine Pharma Today and major employers (CCP, 2011).

Program Experience: Capacity Strengthening

In Liberia, an integrated family planning and immunization program under the Maternal and Child Survival Project (MCSP) conducted a one-day orientation for all supervisors, followed by a three-day training for vaccinators and family planning providers together. The training included a practical component where providers tried out the new approach in a clinical setting. The program also found that including a values clarification component was critical, as many vaccinators were unfamiliar and inexperienced with family planning, and brought in varying levels of bias.

In Liberia, an integrated family planning and immunization program under the Maternal and Child Survival Project (MCSP) conducted a one-day orientation for all supervisors, followed by a three-day training for vaccinators and family planning providers together. The training included a practical component where providers tried out the new approach in a clinical setting. The program also found that including a values clarification component was critical, as many vaccinators were unfamiliar and inexperienced with family planning, and brought in varying levels of bias.

Program Experience: RM&E Plan

Under the Combination Prevention Program for HIV in Central America, PASMO has used a combination prevention approach to deliver HIV prevention social and behavior change messages, products, services and referrals to the key populations most affected by HIV in the region. The program integrates messaging on STIs, gender-based violence and alcohol and drug abuse. In order to measure and demonstrate the effectiveness of the combination prevention approach, PASMO developed a system to track clients through a Unique Identifier Code (UIC). The UIC allows PASMO to maintain client confidentiality, while still ensuring clients are successfully linked to products and services. Read the full case study: Using Unique Identifier Codes to Monitor an Integrated SBCC Program.

Under the Combination Prevention Program for HIV in Central America, PASMO has used a combination prevention approach to deliver HIV prevention social and behavior change messages, products, services and referrals to the key populations most affected by HIV in the region. The program integrates messaging on STIs, gender-based violence and alcohol and drug abuse. In order to measure and demonstrate the effectiveness of the combination prevention approach, PASMO developed a system to track clients through a Unique Identifier Code (UIC). The UIC allows PASMO to maintain client confidentiality, while still ensuring clients are successfully linked to products and services. Read the full case study: Using Unique Identifier Codes to Monitor an Integrated SBCC Program.

Under the Combination Prevention Program for HIV in Central America, PASMO has used a combination prevention approach to deliver HIV prevention social and behavior change messages, products, services and referrals to the key populations most affected by HIV in the region. The program integrates messaging on STIs, gender-based violence and alcohol and drug abuse. In order to measure and demonstrate the effectiveness of the combination prevention approach, PASMO developed a system to track clients through a Unique Identifier Code (UIC). The UIC allows PASMO to maintain client confidentiality, while still ensuring clients are successfully linked to products and services. Read the full case study: Using Unique Identifier Codes to Monitor an Integrated SBCC Program.

Under the Combination Prevention Program for HIV in Central America, PASMO has used a combination prevention approach to deliver HIV prevention social and behavior change messages, products, services and referrals to the key populations most affected by HIV in the region. The program integrates messaging on STIs, gender-based violence and alcohol and drug abuse. In order to measure and demonstrate the effectiveness of the combination prevention approach, PASMO developed a system to track clients through a Unique Identifier Code (UIC). The UIC allows PASMO to maintain client confidentiality, while still ensuring clients are successfully linked to products and services. Read the full case study: Using Unique Identifier Codes to Monitor an Integrated SBCC Program.

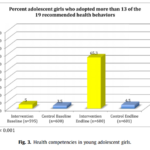

Program Experience: Cluster Randomized Control Design

The Saloni—Seeds of Prevention project used a cluster randomized control design to evaluate an integrated RH, nutrition and hygiene program for adolescent girls aged 11-14 years in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. The Saloni strategy included a 10 session in-school intervention based on compassion, self efficacy, emotional well being, and peer and parental support, packaged in the form of short, easy-to-use instructional modules. A diary designed to engage adolescent girls in managing their own health was provided to each girl. A block of 15 schools was assigned to the intervention arm and another block of 15 schools was assigned to the control arm. A sample of 1200 girls was randomly selected from the two blocks for post-intervention interviews with them and their parents. The intervention had a significant impact on more than 13 preventive health behaviors: 65 percent of girls in the intervention group had adopted 13 or more health behaviors at end line compared to five percent at baseline and to 4.5 percent in the control group at end line. (Source: Kapadia-Kundu N, Storey JD, Safi B, Trivedi G, Tupe R & Narayana G. (2014). Seeds of prevention: The impact on health behaviors of young adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh, India, a cluster randomized control trial. Social Science & Medicine 120, 169-179)

The Saloni—Seeds of Prevention project used a cluster randomized control design to evaluate an integrated RH, nutrition and hygiene program for adolescent girls aged 11-14 years in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. The Saloni strategy included a 10 session in-school intervention based on compassion, self efficacy, emotional well being, and peer and parental support, packaged in the form of short, easy-to-use instructional modules. A diary designed to engage adolescent girls in managing their own health was provided to each girl. A block of 15 schools was assigned to the intervention arm and another block of 15 schools was assigned to the control arm. A sample of 1200 girls was randomly selected from the two blocks for post-intervention interviews with them and their parents. The intervention had a significant impact on more than 13 preventive health behaviors: 65 percent of girls in the intervention group had adopted 13 or more health behaviors at end line compared to five percent at baseline and to 4.5 percent in the control group at end line. (Source: Kapadia-Kundu N, Storey JD, Safi B, Trivedi G, Tupe R & Narayana G. (2014). Seeds of prevention: The impact on health behaviors of young adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh, India, a cluster randomized control trial. Social Science & Medicine 120, 169-179)

Program Experience: Quasi-Experimental Design

The Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) program in Egypt (2003-2010) used a quasi-experimental impact evaluation design to evaluate the added value of community-based outreach and mobilization on top of a national mass media campaign around a diverse set of lifestage-specific family health issues. In the Minya Governorate, five villages were designated as treatment sites and two additional villages of comparable size and health status were designated as comparison sites. All villages throughout the country, including the Minya control villages, received the national package of media interventions, while only the treatment villages received a community-based outreach and mobilization program implemented by local civil society organizations. This allowed comparisons between “program villages” (media plus community-based) and “non-program villages” (media only) with statistical controls to account for exposure bias (Hutchinson & Meekers, 2012).

The Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) program in Egypt (2003-2010) used a quasi-experimental impact evaluation design to evaluate the added value of community-based outreach and mobilization on top of a national mass media campaign around a diverse set of lifestage-specific family health issues. In the Minya Governorate, five villages were designated as treatment sites and two additional villages of comparable size and health status were designated as comparison sites. All villages throughout the country, including the Minya control villages, received the national package of media interventions, while only the treatment villages received a community-based outreach and mobilization program implemented by local civil society organizations. This allowed comparisons between “program villages” (media plus community-based) and “non-program villages” (media only) with statistical controls to account for exposure bias (Hutchinson & Meekers, 2012).

Development Media International (DMI) used a non-randomized, controlled before and after study design to test a mobile phone intervention in southwest Burkina Faso (2014-2015). Using an entertainment education approach, DMI produced eight short (3-minute) videos on mobile phones for primary care givers. The videos were shared by mobile phone distributors and promoted four key behaviors related to malaria, hygiene, pneumonia, and diarrhea. The study tested the reach and impact of the intervention by choosing nine intervention and ten control villages in the Gaoua region – an area where traditional media channels were not available. Study results showed that 32% of women and 46% of men in the target area had seen the films, and there was evidence that the videos were shared. (Source: http://www.developmentmedia.net/burkina-faso-mobile-phone-videos-trial.html)

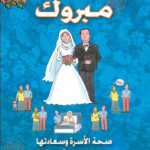

Program Experience: Panel Survey

The Mabrouk! (Congratulations!) Initiative, which was part of the integrated Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) project in Egypt (2003-2010), used a family lifestage approach to help families anticipate and respond positively to the interrelated antenatal, safe delivery, neonatal, postpartum, early childhood and lifestyle health issues they would soon face. The impact evaluation used a three-wave panel survey (2004, 2005, 2008) of women, their husbands and unmarried young adults in the same household, all interviewed at three points in time, to measure how household members responded to these issues over a four year period. The panel survey helped the program measure the cumulative impact of messaging on multiple topics as the phases of the intervention were introduced. It also permitted study of “health competence”, that is, how an increase in knowledge, attitudes and resources related to healthy practices at an early stage of the project facilitated response to new health issues as they the arose. For example, when avian influenza broke out in 2006, families with higher health competence were better prepared to initiate protective actions. Panel designs have another advantage: because they compare the same people with themselves over time, respondent background characteristics remain constant, thus controlling for variations in the study population and strengthening causal inferences.

The Mabrouk! (Congratulations!) Initiative, which was part of the integrated Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) project in Egypt (2003-2010), used a family lifestage approach to help families anticipate and respond positively to the interrelated antenatal, safe delivery, neonatal, postpartum, early childhood and lifestyle health issues they would soon face. The impact evaluation used a three-wave panel survey (2004, 2005, 2008) of women, their husbands and unmarried young adults in the same household, all interviewed at three points in time, to measure how household members responded to these issues over a four year period. The panel survey helped the program measure the cumulative impact of messaging on multiple topics as the phases of the intervention were introduced. It also permitted study of “health competence”, that is, how an increase in knowledge, attitudes and resources related to healthy practices at an early stage of the project facilitated response to new health issues as they the arose. For example, when avian influenza broke out in 2006, families with higher health competence were better prepared to initiate protective actions. Panel designs have another advantage: because they compare the same people with themselves over time, respondent background characteristics remain constant, thus controlling for variations in the study population and strengthening causal inferences.

Program Experience: Dose Response

The Gateway Behaviors Project in Nigeria (2012-2015) was designed to test the hypothesis that antenatal care (ANC) utilization and spousal communication (the “gateway” behaviors) could have a multiplier effect, catalyzing a whole range of perinatal health behaviors. To promote those two gateway behaviors, the project implemented an integrated set of messages including community signage and public dialogue sessions, parades and performances, door-to-door mobilization & referrals to services, SMS blasts, and communication training for service providers. The endline survey found that the more sources of exposure to Gateway messages that a woman reported, the greater the probability that she had gone for ANC and had talked to her partner about perinatal health. She was also more likely to report each of six different perinatal behaviors: delivering her most recent child in a health facility, having a medically assisted delivery, adopting postpartum FP, initiating breastfeeding immediately after delivery, getting an HIV test, and fully vaccinating her youngest child. For example, only 20% of women who reported the lowest level of message exposure reported getting a perinatal HIV test compared to 60% of women who reported the highest level of message exposure. Furthermore, women who neither had 4 or more ANC visits nor talked to her partner about perinatal health reported practicing an average of 2.8 perinatal behaviors, while women who had 4 or more ANC visits and talked to her partner about perinatal health reported an average of 4.5 perinatal health behaviors (Source: Storey JD, Adefioye O, Bamidele M & Awantang G. (2015). NURHI Gateways Supplement Evaluation Report. Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Baltimore, MD.)

The Gateway Behaviors Project in Nigeria (2012-2015) was designed to test the hypothesis that antenatal care (ANC) utilization and spousal communication (the “gateway” behaviors) could have a multiplier effect, catalyzing a whole range of perinatal health behaviors. To promote those two gateway behaviors, the project implemented an integrated set of messages including community signage and public dialogue sessions, parades and performances, door-to-door mobilization & referrals to services, SMS blasts, and communication training for service providers. The endline survey found that the more sources of exposure to Gateway messages that a woman reported, the greater the probability that she had gone for ANC and had talked to her partner about perinatal health. She was also more likely to report each of six different perinatal behaviors: delivering her most recent child in a health facility, having a medically assisted delivery, adopting postpartum FP, initiating breastfeeding immediately after delivery, getting an HIV test, and fully vaccinating her youngest child. For example, only 20% of women who reported the lowest level of message exposure reported getting a perinatal HIV test compared to 60% of women who reported the highest level of message exposure. Furthermore, women who neither had 4 or more ANC visits nor talked to her partner about perinatal health reported practicing an average of 2.8 perinatal behaviors, while women who had 4 or more ANC visits and talked to her partner about perinatal health reported an average of 4.5 perinatal health behaviors (Source: Storey JD, Adefioye O, Bamidele M & Awantang G. (2015). NURHI Gateways Supplement Evaluation Report. Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Baltimore, MD.)

Program Experience: Social Network Analysis

Impact evaluation of the Radio Communication Project in Nepal (1994-2002) used social network analysis to understand the indirect or “pass along” effects of a national family health radio drama. In randomly selected villages, all women of reproductive age were interviewed and asked to identify which other women in the community they talked to about family health, as well as about their exposure to the RCP radio drama. In the sociogram of each village’s network, women were identified who had listened to the radio drama or not and whether or not they talked to someone who listened to the drama. Analysis revealed that non-listeners who had talked to listeners were just as likely to report key family health behaviors (e.g., contraceptive use, Vitamin A consumption) as women who had listened to the drama. Both were more likely to report those behaviors than non-listeners who did not report talking to listeners. (Source: Storey JD, Boulay M, Karki Y, Heckert K & Karmacharya DM. (1999). “Impact of the Integrated Radio Communication Project in Nepal, 1994-1997.” Journal of Health Communication, 4: 271-294.)

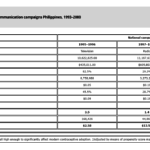

Program Experience: Cost Effectiveness

A series of three national family planning campaigns in the Philippines between 1995-2001 that differed in terms of the channels of communication used, presented an opportunity to compare the cost effectiveness of different media channels (Kincaid & Do, 2006). Although these campaigns were not integrated in a cross-sectoral sense, the methodological approach could be applied just as well to comparisons of different integration strategies. The first campaign in 1995-1996 relied heavily on television to deliver its messages, but in 1997-1998, because of political and religious pressure, the government decided to use radio instead of television in order to keep a lower profile. The program returned to the use of television in 2000-2001. The impact of the campaigns was assessed using nationally representative population-based surveys that made it possible to extrapolate to the number of Filipinos who were exposed to the campaigns and who reported initiation of contraceptive use. The costs of developing, producing and disseminating the media materials (including the cost of airtime) was divided by the number of new adopters attributed to each wave of the campaign, producing a unit cost of reaching each person and achieving FP adoption. Because of the dramatically greater reach of television versus radio, it cost less to reach each person (about 5-6 cents for television versus 19 cents for radio) and to change FP behavior (less than USD 3 for television versus more than USD 13 for radio).

A series of three national family planning campaigns in the Philippines between 1995-2001 that differed in terms of the channels of communication used, presented an opportunity to compare the cost effectiveness of different media channels (Kincaid & Do, 2006). Although these campaigns were not integrated in a cross-sectoral sense, the methodological approach could be applied just as well to comparisons of different integration strategies. The first campaign in 1995-1996 relied heavily on television to deliver its messages, but in 1997-1998, because of political and religious pressure, the government decided to use radio instead of television in order to keep a lower profile. The program returned to the use of television in 2000-2001. The impact of the campaigns was assessed using nationally representative population-based surveys that made it possible to extrapolate to the number of Filipinos who were exposed to the campaigns and who reported initiation of contraceptive use. The costs of developing, producing and disseminating the media materials (including the cost of airtime) was divided by the number of new adopters attributed to each wave of the campaign, producing a unit cost of reaching each person and achieving FP adoption. Because of the dramatically greater reach of television versus radio, it cost less to reach each person (about 5-6 cents for television versus 19 cents for radio) and to change FP behavior (less than USD 3 for television versus more than USD 13 for radio).

Program Experience: Case Studies

In Tanzania, listeners of the Kamiligado radio distance learning program submitted examples of how they felt their communities had benefitted from the program by SMS. Among those that submitted their MSC stories, 35 were selected to be profiled in written pieces, and of those, 15 were selected for in-depth interviews. The in-depth interviews revealed the dramatic impact of Kamiligado, and potential impact of other similar programs in Tanzania and elsewhere. Read the Kamiligado listener’s stories here.

In Tanzania, listeners of the Kamiligado radio distance learning program submitted examples of how they felt their communities had benefitted from the program by SMS. Among those that submitted their MSC stories, 35 were selected to be profiled in written pieces, and of those, 15 were selected for in-depth interviews. The in-depth interviews revealed the dramatic impact of Kamiligado, and potential impact of other similar programs in Tanzania and elsewhere. Read the Kamiligado listener’s stories here.