Components of an Integrated SBCC Strategy

Components of an Integrated SBCC Strategy

The structure and components of an integrated SBCC strategy do not differ from that of a vertical program. However, the content of each of the components may be quite different from vertical programs. In this section you will find special considerations for each of the components of an integrated SBCC strategy.

Goals and Objectives

Goals and objectives are designed to state the intended impact of the communication program. The goals of an integrated SBCC program should flow from the shared vision agreed on by stakeholders. The goals should be bigger than what a single-focus SBCC effort could accomplish and answer the question: “If major progress is made on all of the issues/behaviors addressed through this program, what will be the result?” In addition, the objectives should implicitly or explicitly cover all of the health or development topics and behaviors included in the integrated effort. Ideally, the objectives will reinforce each other.

Project: USAID-funded World Relief/Burundi Ramba Kibongo (Live Long Child) Program

Goal: To reduce the morbidity and mortality among children under five years of age and women of reproductive age.

Areas covered: Nutrition, malaria, diarrhea, immunization and family planning

Objectives:

- Improved linkages between households, communities and the formal health system

- Improved availability and access to essential health commodities at the community level

- Increased knowledge and adoption of key family practices for child health by child caregivers with support from community leaders and health providers

Theory and Frameworks

Grounding any SBCC strategy in a theoretical model is important but it can be even more so for an integrated program. A theoretical model lays out a “map” of how and why you expect change to happen. It helps to focus and guide every aspect of the program – from design to implementation and M&E. Given the complexity of an integrated SBCC program, a sound theoretical model can help stakeholders understand the logic behind program decisions and how each partner fits into the overall strategy.

Below is a selection of theoretical models that have been applied to integrated SBCC programs:

The Socio-Ecological Model is an appropriate model for many multi-sectoral approaches, due in part to its breadth and flexibility.

Examples: Two examples include the Pan American Social Marketing Organization’s (PASMO) COMBI-PREV program and Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program (HEP).

In Central America, COMBI-PREV aimed to provide populations most at risk for HIV with at least three interventions, including behavior change communication (e.g., participative methodologies and access to condoms and lubricants), effective biomedical services (e.g., HIV testing and counseling and sexually transmitted infection [STI] screening) and referral to complementary or structural services (e.g. family planning, violence prevention services and human rights and legal services).

Ethiopia’s HEP spans every level of change. The “women’s development army” consists of community-level volunteers who spark behavior change on a local, individual level. These volunteers are trained by extension workers, who are stationed at rural health posts. The country’s nationwide referral network links these posts to larger, better-equipped health centers, and the health centers to hospitals. The women-centered health system creates linkages at and between every level, from village to national.

The Pathways Model™ also addresses multiple levels of impact, multiple audiences and emphasizes facilitating factors that cut across impact areas.

Example: For instance in Mozambique, the Health Communication Partnership project (2002-2007) used a Pathways Model to address family planning and MCH.

Health Competence focuses on the individual’s ability to demand or use health services appropriately or adopt health practices, and can be used across a number of different topics or behaviors. Once health competence is built in one life stage, and an individual achieves specific, visible health results and the resultant improved self-efficacy then carries over to future life stages.

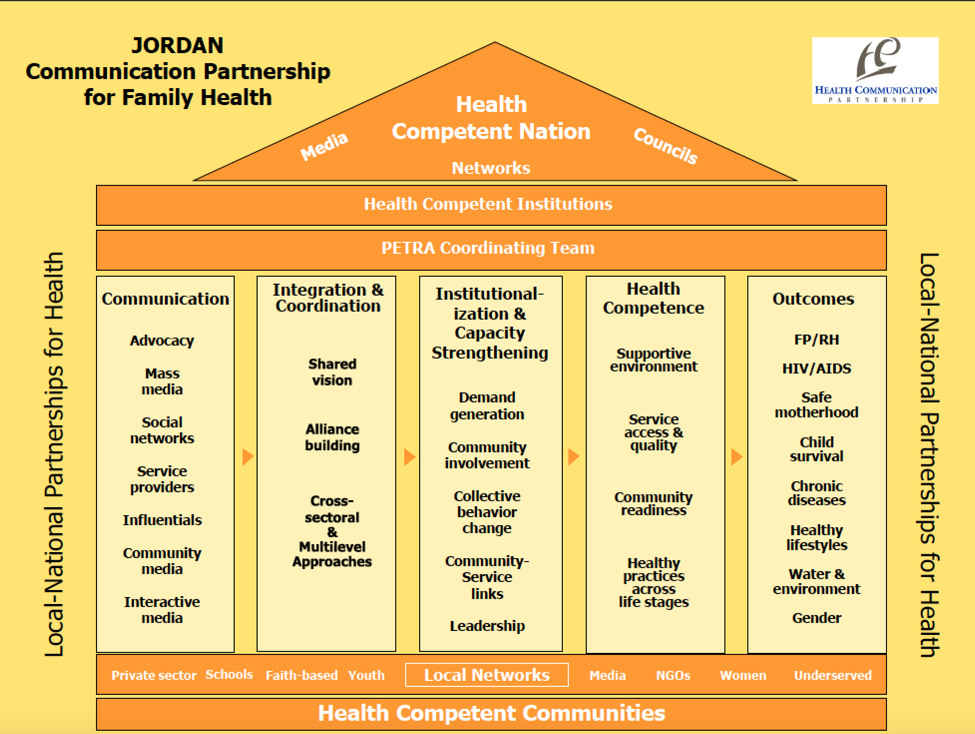

Example: The Jordan Health Communication Partnership used a Health Competence framework to guide its integrated programming.

Bounded Normative Influence (BNI) is a group-level theory that explains how a minority can influence the majority. BNI “is the tendency of social norms to influence behavior within relatively bounded, local subgroups of a social system rather than the system as a whole.” A minority position can become the social norm when certain criteria are met – namely, when the minority maintains a majority status within its own, locally bounded portion of the network, allowing it to persist, to recruit adapters in the vicinity and to ultimately establish its behavior or position as the norm for the entire network.

Example: In Mozambique, Tchova Tchova Historias de Vida (TTHV) used BNI for its design and evaluation, with couples and communities as its bounded subgroups. TTHV used real story videos to engage community members and couples in an open discussion and debate about sexual and gender norms. Through organized community group discussions, married couples were invited to participate in nine sessions that addressed a variety of issues related to HIV risk behaviors. While the project focused on HIV, the application of BNI in Tchova Tchova may have wider significance for integrated projects.

Social Learning Theory offers a narrative lens and behavioral modeling, which lends itself well to multiple topics. With the premise that people learn through observing the behaviors, attitudes and behavioral outcomes of those that are similar to themselves.

Example: TCCP created an entertainment-education television serial drama, Siri ya Mtungi (Secrets of the African Pot). The drama used subtle messaging, gripping storylines, and a colorful cast of characters to integrate SBCC messaging around HIV testing and counseling, condom use, the reduction of concurrent sexual partners, PMTCT, maternal and child health, and the adoption of modern family planning methods. Siri ya Mtungi used Social Learning Theory to follow the characters through multiple stages of behavior change, modeling how positive behaviors can be adopted over time – and how behavior change is not necessarily a straightforward, linear process. To that end, Stages of Change can be useful for looking at how far along a continuum audiences are in modeling behavior, and can facilitate segmentation beyond traditional means.

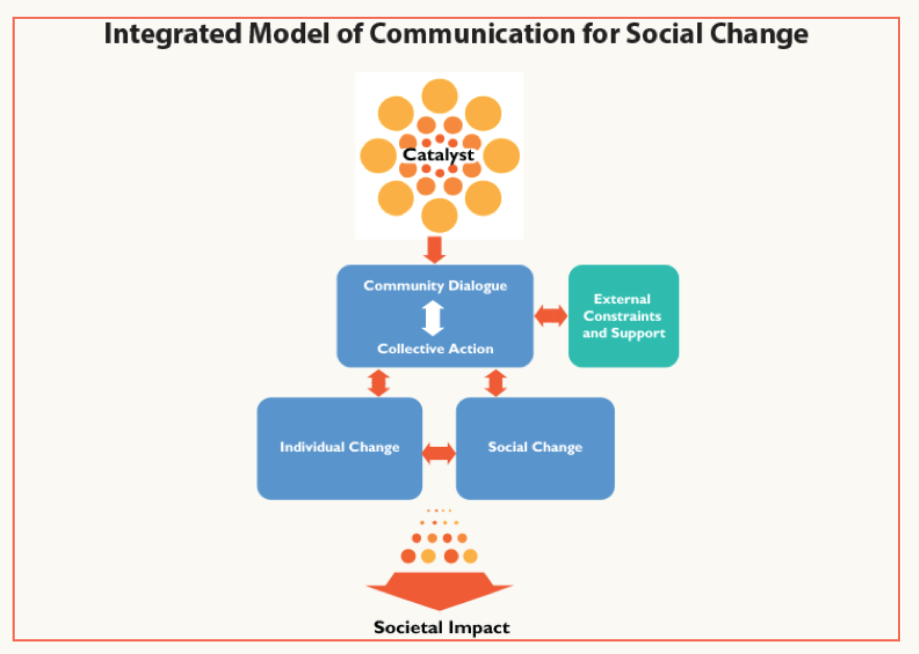

Communication for Social Change (C4SC) is an iterative process where “community dialogue” and “collective action” work together to produce social change in a community to improve the health and welfare of all its members.

Example: Ghana’s Behavior Change Support (BCS) project employed a C4SC model to blend community, interpersonal and mass media approaches across all of its health areas to integrate its four program elements: behavior change communication; community mobilization; systems strengthening; and capacity building. As part of its strategy development process, BCS fostered partnerships among key stakeholders, including the Ghana Health Service/Family Health Division, USAID, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and key program implementers.

The Theory of Planned Behavior considers three types of beliefs that tend to guide human behavior:

- Behavioral beliefs, which consider the positive and negative outcomes of the decision

- Normative beliefs, which result in perceived social pressure or subjective norms

- Control beliefs, which help determine self-efficacy, or confidence in one’s ability to perform the behavior

When combined, the three types of beliefs result in the formation of an intention to engage in the behavior (or not). This theory may work well when your goal is to create logical linkages between different topics and behaviors (Source: HC3, 2014).

Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) helps explain and predict factors that influence the adoption of innovations such as products, services or ideas over time. Successful innovations typically spread from a few innovators and early adopters to the rest of the population – early majority, late majority and laggards. Understanding the characteristics of each of these types of adopters can help you apply different strategies to each segment. DOI might be useful for rapid behavior change, especially when used with Social Network Analysis (SNA) or the Positive Deviance Approach (PDA). SNA provides a visual and mathematical analysis of human relationships, showing where there are clusters or groupings in a network, who is in the core of the network, who is on the periphery and who takes on various roles (e.g., connectors, mavens, leaders, bridges and isolates). PDA, on the other hand, identifies people or groups whose “special or uncommon behaviors or strategies enable him/her/them to overcome a problem without special resources and facing similar barriers and challenges as their peers.”

Example: During the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, DOI helpedencourage rapid behavior change. By training and equipping community volunteers and local leaders who were well respected, the HC3 team was able to quickly spread or “diffuse” correct information and positive health behaviors like safe burials throughout the community. These local leaders served as thought leaders and early adopters in their communities who then spread these new ideas to community members. Ebola messages were integrated with sanitation, hygiene and infection control messages that had already been promoted in Total Sanitation communities and among child survival programs.

Other programs have combined theories or developed their own, based, for example, on how bringing the different topics/behaviors together should lead to greater overall change.

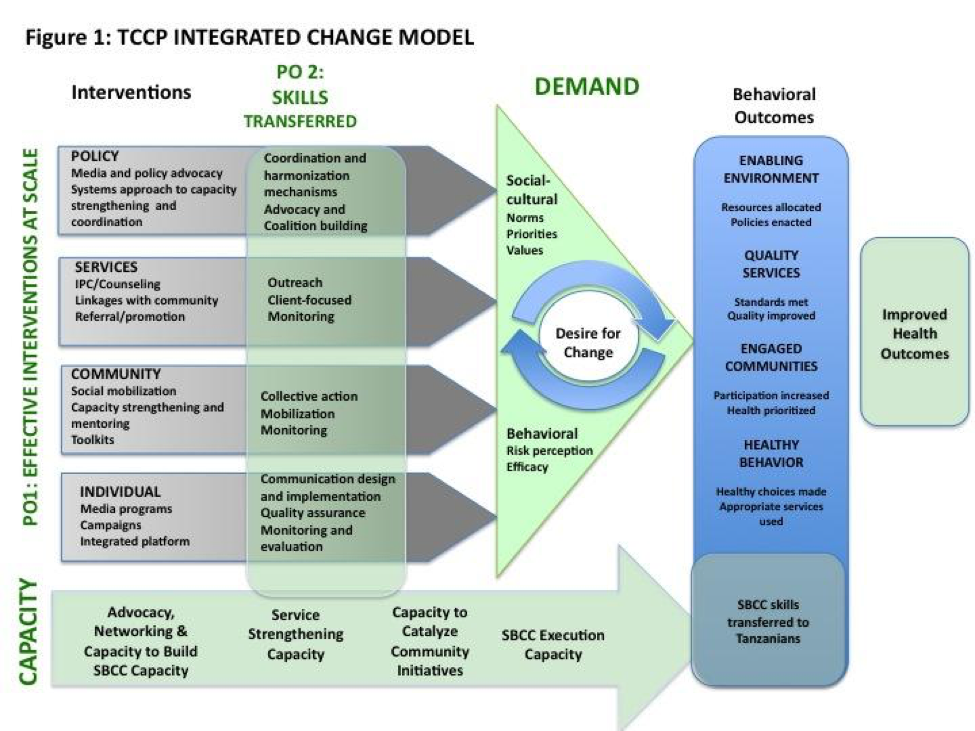

Example: One example of this is the TCCP Integrated Change Model. Central to the model was the belief that creating desire for change across all levels of society is at the heart of real progress. Multi-level communication strategies and interventions operated at the policy, community, family and individual levels. The model posited that, together, the interventions would catalyze demand by shifting perceptions of risk and efficacy at the individual behavioral level and norms and priorities at the socio-political and cultural levels.

Approaches to Integrated SBCC

While the theory helps you explain why and how your program should work, the approach provides an overarching method for carrying out your integrated program. The field of integrated SBCC is evolving and new approaches are continually emerging.

Below are some approaches that have been implemented successfully:

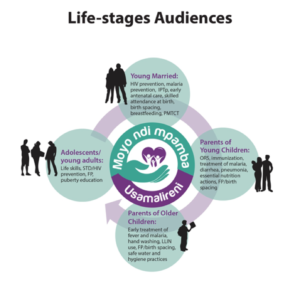

In the Life Stages Approach, programs reach audiences with information and skills that are relevant to their stage in life, in the belief that providing audiences with information they need when they need it increases the likelihood of its use. The Life Stage approach segments the family and society as a whole according to the age- or stage-appropriate needs of each member, addressing the household as a key decision-making unit. This approach acknowledges that each life stage, while transitional, has its own specific behavioral objectives and health needs. Promoting positive health behavior at early stages represents a positive health investment and will have a cumulative, sustainable impact on future health behavior. Additionally, healthy behaviors adopted within a family will, by extension, improve the health status of the larger community (JHCP Project Report, 2013).

Examples: In Malawi, for example, SSDI developed their communication strategy around four key life stages: young married couples, parents with children under five, parents with older children and adolescents. The four life stages were adopted by all three SSDI projects–SSDI-Communication, SSDI-Services and SSDI-Systems (Source: HC3, 2016).

Examples: In Malawi, for example, SSDI developed their communication strategy around four key life stages: young married couples, parents with children under five, parents with older children and adolescents. The four life stages were adopted by all three SSDI projects–SSDI-Communication, SSDI-Services and SSDI-Systems (Source: HC3, 2016).

Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) in Egypt also used a Life Stages approach to address family members from birth through old age, with a special focus on newly married and young couples. CHL aimed to address a wide range of health areas using the Life Stages approach, including family planning, reproductive health, MCH, infectious diseases (including HIV) and healthy lifestyles and practices.

Communication for Healthy Living (CHL) in Egypt also used a Life Stages approach to address family members from birth through old age, with a special focus on newly married and young couples. CHL aimed to address a wide range of health areas using the Life Stages approach, including family planning, reproductive health, MCH, infectious diseases (including HIV) and healthy lifestyles and practices.

Communication for Healthy Communities (CHC) in Uganda was based on the Life Cycle/Life Stage approach. Due to its personal touch, the approach triggered rapport, honest dialogue and self-reflection and provided knowledge, motivation and skills on HIV prevention, HIV care and treatment, MCH, nutrition, family planning, malaria and TB. The interventions were aimed at shifting gender and social norms and providing supportive environments for adopting recommended heath actions/behaviors. They were implemented through targeted interpersonal communication (IPC), community mobilization interventions, mass media and social media as well as print and outdoor media.

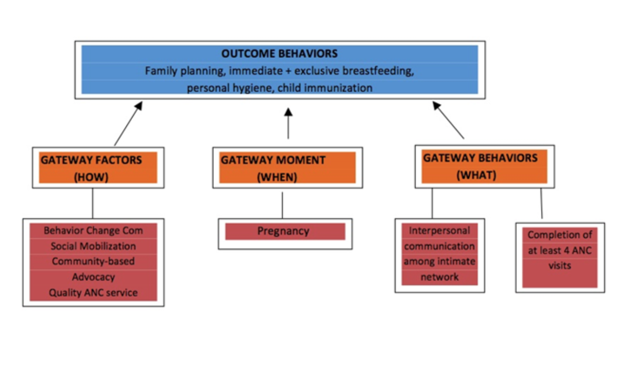

Gateway Behavior or Moment Approach: “Gateway” refers to a positive health behavior or to a facilitating factor that may trigger or facilitate other positive health behaviors, both simultaneously and across the family life cycle. For example, getting women to attend ANC can then lead to IPTp uptake, HIV testing, birth planning and other healthy behaviors.

Examples: In Bangladesh, Alive and Thrive has worked to integrated maternal nutrition into a large-scale MNCH program with the idea that maternal nutrition is a gateway to positive infant and young child feeding outcomes.

The Nigeria Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) used a gateway behavior approach to promote two key behaviors – completion of all recommended ANC visits and IPC on family health matters – with the hypothesis that adoption of these behaviors had significant potential to then facilitate the adoption of other health behaviors, including family planning, exclusive breastfeeding and immunization.

Behavioral Attributes Approach: The behavioral attributes approach takes into account that behaviors from different health or development topics may have more in common than behaviors from the same health area. For example, messaging about daily adherence to both antiretrovirals (ARVs) (HIV) and oral contraceptive pills (family planning) might be more similar than messages about ARV adherence and CD4 testing, which are both part of an HIV program.

To determine which behaviors might be promoted together, examine their attributes (i.e., the characteristics that define the behavior). Analyze the similarities and differences across the health areas and behaviors in your intended program to determine if there are ways to combine and package content that will improve impact, economies of scale, cost-effectiveness or program efficiency. Consider these potential points of convergence or divergence when determining which health areas and/or behaviors to package together.

Points to Consider:

- What is the frequency of the behaviors you are looking to influence – daily, weekly, monthly or yearly? Are they one-time behaviors (e.g., voluntary medical male circumcision), behaviors enacted for a certain period of time (e.g., exclusive breastfeeding for six months) or practices the audience is familiar with? Are the behaviors habitual, or do they require a deliberative process? Are you aiming to increase the behaviors (e.g., exercise), decrease the behaviors (e.g., reduce sugar consumption) or stop a behavior completely (e.g., smoking)? What time of the day do the behaviors happen (e.g., morning, evening or at multiple time points)?

- What are the financial, logistical and social costs of the behaviors? Are they costly? Cheap? Free? How easy or complicated are the behaviors? Are they stigmatizing or pride-inducing?

- Do similar structural (e.g., distance to the health facility, infrastructure, law or policy) or ideational (e.g., attitudes, couple communication, self-efficacy or social ties) factors affect the behavior?

- Are the behaviors done publicly or in private? Do the behaviors require the agreement or support of others, or can they be done alone? Are there any concerns around anonymity (e.g., HIV testing and counseling)?

- Are the behaviors shaped by gender norms, inequality or other social factors? Is the behavior of high cultural significance (e.g., traditional male circumcision)?

- If behaviors require interaction with a health provider, what needs to happen before, during and after the client-provider interaction (e.g., demand creation, quality counseling and adherence, respectively)?

These behavioral attributes can affect messaging, timing, phasing, channel selection and other parts of the strategy (Source: Adapted from Rajiv’s SBCC Summit presentation).

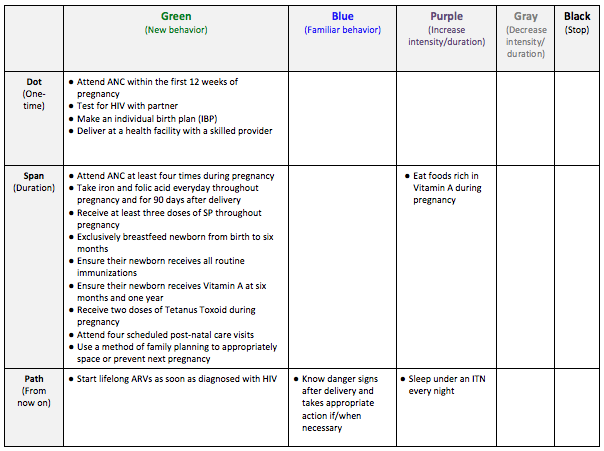

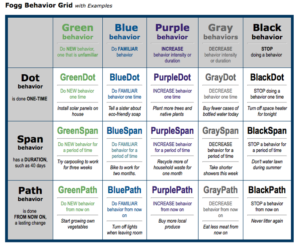

Example:  In Tanzania, the Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign used the Fogg Behavioral Model to inform its design. The Fogg model posits that there are three different durations of behaviors – one-time, over a limited period of time and indefinitely – and five different behavioral categories (a new/unfamiliar behavior, a familiar behavior, increasing behavior, decreasing behavior and ceasing behavior). This results in a grid of 15 possible types of behaviors (shown below). The design team mapped each of the campaign’s desired behaviors onto the grid in order to better understand their attributes, and, in turn, how to best address the target audience and trigger change (Source: Fogg, 2010).

In Tanzania, the Wazazi Nipendeni safe motherhood campaign used the Fogg Behavioral Model to inform its design. The Fogg model posits that there are three different durations of behaviors – one-time, over a limited period of time and indefinitely – and five different behavioral categories (a new/unfamiliar behavior, a familiar behavior, increasing behavior, decreasing behavior and ceasing behavior). This results in a grid of 15 possible types of behaviors (shown below). The design team mapped each of the campaign’s desired behaviors onto the grid in order to better understand their attributes, and, in turn, how to best address the target audience and trigger change (Source: Fogg, 2010).

(Sources: TCCP Program Documents).

Some integrated SBCC efforts focus on targeting behaviors that tend to occur together. Common examples include HIV and TB prevention and control, and HIV and substance abuse prevention. SBCC efforts often seek to address common drivers of co-existing behaviors, use entry points accessed for one issue to address the other issue(s) and link the issues/behaviors in the minds of the audiences.

Often, programs seek to broaden a behavior change effort by adding new health areas onto an existing health program. This allows the program to take advantage of existing buy-in, structures and platforms. Examples include integrating family planning into immunization and other child health programs, integrating HIV into family planning or vice versa, and integrating maternal and child nutrition into child health programs.

Tip

Social norms are critical to integrated programs, but shifting them can take a long time. Given the breadth of integrated programming, carefully consider how best (and how much) to emphasize social change. It can be helpful to identify norms that are shared across health topics and then determine which are most critical to address. Programs might have to rely on changes in attitude and/or on individual behavior change as shorter-term proxies for social change.

Attention

Definition

Co-occurrence is an attribute of certain behaviors. Thus, co-occurrence can be considered a subsidiary of the behavioral attributes approach.

Target Audience

Integrating SBCC can complicate audience identification and segmentation. It might also reveal overlooked audiences. It is important to use what is known in the literature and discovered during formative research to identify and prioritize audiences, understanding that priority and influencing audiences might differ according to the topic or behavior.

If using an umbrella approach, you may find there is a core audience for the overarching brand, and more specific, segmented audiences for each technical intervention. Ghana’s GoodLife “umbrella” brand, for example, targeted young families. The specific target audience would then vary slightly for each different health campaign. For example, pregnant women were a primary target audience and mothers/mother-in-laws were a secondary target audience for the IPTp campaign.

Integrated SBCC may be particularly relevant for certain audiences, such as adolescents as the focus of a reproductive health project, who would need (and likely welcome) information not only about contraceptives but also about sexual debut, marriage, education, livelihoods, HIV and more.

Consider what types of audience segmentation might make sense for your integrated SBCC program. If you are using a Life Stages approach, you may segment by key life stages, such as adolescence, marriage, pregnancy and parenthood. Some of these stages can be broken down even further, depending on the program’s needs. Parenthood, for instance, may include the pregnancy period, parents of newborns, parents of infants and parents of children ages two to five -years old. If your program is grounded in the Stages of Change, you may look to segment by readiness to adopt a behavior. As multiple behaviors are implicated in integrated programs, a “readiness index” that assesses the stage of change across all behaviors might be appropriate. Possibilities for audience segmentation are nearly endless. See How to Do an Audience Analysis and How to Do Audience Segmentation for more information.

On the other hand, you may find a need to collapse target audiences into broader categories in order to achieve efficiencies. Be prepared to lose the specificity of your target audience in order to gain effectiveness.

Content and Messaging

When developing content for an integrated program, it is particularly important to think about how you will prioritize and package the content. In other words,

- Prioritize: Which health topics or behavioral messages will be rolled out first? Which will be rolled out last? How much time will be given to each topic area? Which content is most important and absolutely must be included in the program? Which content might be cut?

- Package: Which health topics will be bundled together? Which behavioral actions might be combined within one message?

How to Prioritize and Package Content

Deciding how to prioritize or package content for an integrated SBCC program can be complicated. Which content do you keep? What do you sacrifice for the sake of focus? What do you focus on first? Do certain topics or behaviors deserve more attention than others? How do you ensure your messages are well-balanced, coherent, logically packaged and rolled out in an understandable way?

Programs have used a variety of approaches for prioritizing and packaging content in integrated strategies. As noted above, some use a phased approach, which helps balance the amount of information being conveyed at once. For example, a phased approach can start with messages about behaviors considered to be relatively easy to adopt (i.e., “low-hanging fruit” or small, doable actions), as determined by formative research, or with the topic whose funding ends first/earliest. If possible, plan to repeat the cycle of messages to reinforce them. Unfortunately, in situations where multiple donors or vertical programs are involved, phasing can be difficult.

Ultimately, you are aiming to create synergy by addressing related topics together. Consider the following methods of combining or prioritizing SBCC content.

- What are the behavioral determinants that influence the adoption of each behavior, and how might you focus messaging on these?

- How simple or complex are the different behaviors? Complex behaviors may need more in-depth messaging or attention.

- What are the other attributes of your behaviors? How might this influence messaging? (See Behavioral Attribute Approach)

- What are the causal pathways of your behaviors? What gateway behavior(s) lead to others?

- How might you use participatory methods such as human-centered design or the Action Media methodology to determine what information end users want to receive, how they want to receive it and in which order?

- What are the client’s most immediate needs? For example, if a client comes for family planning, start with family planning, then move to other issues of concern such as HIV testing, post-natal care or immunization.

- What topics or behaviors could be addressed during key “teachable moments” in a family’s life?

- How does the community prioritize these topics and outcomes? What would help them see the link between various topics or behaviors?

- What does the evidence say about what might lead to the best outcomes in terms of packaging content? What has worked (or failed) elsewhere?

- Where are there information gaps or rising needs?

- What guidance does your theory of change and/or approach offer in how to package messages?

- What are the health or development outcome priorities of the host country and the donor?

- What is the level of funding for each topic?

- How do your topics or behaviors relate to one another epidemiologically? In the minds and lives of the audience? In the delivery of products and/or services?

- What is the availability of relevant products, services and/or support structures? Encouraging behaviors that cannot be practiced can create frustration.

- What is the capacity of the health provider or community health worker to address these topics? You may want to start with familiar topics or messages and build from there.

Definitions

Tip

When it comes to SBCC integration, focus demands sacrifice – even more so than in vertical programs. In deciding how many messages to convey in a single intervention, such as a counseling session or radio drama, consider both the audience and the channel. Some research shows people can retain just three key messages discussed in a 15-minute session.

Message Harmonization

While messages are an integral part of your communication strategy and will be addressed during the strategy design, you may find you need to dedicate extra time to this component.

Hold a message development workshop with partners and stakeholders to help ensure messages are harmonized, agreed upon and that partners feel their messages are represented well.

- Organizing this workshop may best be assigned to a working group, task force or other sub-group of the coordinating body.

- Be sure to include technical experts from each topical area in the workshop to help ensure technical accuracy.

- Consider developing a message guide or matrix to harmonize all messages moving forward.

See the HC3 guide on How to Design SBCC Messages. The list of Resources at the end of this section provides examples of how integrated SBCC projects have harmonized messages.

- What are the behavioral determinants that influence the adoption of each behavior, and how might you focus messaging on these?

- How simple or complex are the different behaviors? Complex behaviors may need more in-depth messaging or attention.

- What are the other attributes of your behaviors? How might this influence messaging? (See Behavioral Attribute Approach)

- What are the causal pathways of your behaviors? What gateway behavior(s) lead to others?

- How might you use participatory methods such as human-centered design or the Action Media methodology to determine what information end users want to receive, how they want to receive it and in which order?

- What are the client’s most immediate needs? For example, if a client comes for family planning, start with family planning, then move to other issues of concern such as HIV testing, post-natal care or immunization.

- What topics or behaviors could be addressed during key “teachable moments” in a family’s life?

- How does the community prioritize these topics and outcomes? What would help them see the link between various topics or behaviors?

- What does the evidence say about what might lead to the best outcomes in terms of packaging content? What has worked (or failed) elsewhere?

- Where are there information gaps or rising needs?

- What guidance does your theory of change and/or approach offer in how to package messages?

- What are the health or development outcome priorities of the host country and the donor?

- What is the level of funding for each topic?

- How do your topics or behaviors relate to one another epidemiologically? In the minds and lives of the audience? In the delivery of products and/or services?

- What is the availability of relevant products, services and/or support structures? Encouraging behaviors that cannot be practiced can create frustration.

- What is the capacity of the health provider or community health worker to address these topics? You may want to start with familiar topics or messages and build from there.

Channel Selection

As with any SBCC program, the choice of channel(s) should depend on the audiences, the purpose/desired outcome and the type of information being conveyed. Similarly, it is important to ensure message consistency across all channels. See HC3’s guide on how to develop a channel mix plan here.

- Consider which channels lend themselves to certain audiences, types of content or communication objectives. IPC and community mobilization, for example, are often effective in addressing social norms. Experiential channels where the audience has the opportunity to try behaviors or skills, meanwhile, may be most appropriate for addressing habits. Mass media channels are often a good choice for planning or service-seeking behaviors.

- Consider formats that can easily include several issues, such as radio or TV serial dramas, magazine programs or distance learning programs.

- Balance the breadth, depth and intensity of messages across different media, so that channels will not be overburdened.

- Complement or supplement IPC channels (e.g., CHWS and facility-based providers) with other channels to avoid overloading personnel.

- Facilitate easy access to information for CHWs and facility-based providers to enable them to communicate effectively on the varied topics. Materials for clients and job aids – particularly ones that are easily accessible via cell phone or tablet – can help in this regard.

- Ensure effective IPC to help explore the variety of issues and links between them. Use other channels to generate demand and reinforce messages delivered through IPC.

- Utilize longer formats and more interactive channels for complex behaviors that are more difficult to change. Shorter format channels (e.g., radio or TV spots) may be more appropriate for simpler behaviors more in need of reminders.

Tip

Studies of integrated SBCC projects found IPC to be highly effective when communicating multiple messages. One key is to ensure that those delivering the messages exercise critical thinking skills and can tailor messages to the individuals with whom they interact/to each client, based on client needs.

Tip

One approach to channel selection might be to have an SBCC “centerpiece” or flagship platform that helps frame the messaging and engage individuals and households, such as a radio program or a TV game show.

Program Experiences

- At the start of the Nuru integrated poverty reduction program in Kenya, the agriculture program targeted farmers, the financial inclusion program targeted entrepreneurs and the WASH, healthcare and education programs targeted the entire community. This caused Nuru to question how this assortment of programs focused in the same community was getting at people of extreme poverty faster, cheaper and more effectively than any one of the interventions alone. As a result, they changed their unit of impact to the farmer and their household, with all outcomes focused at aggregated up to that level. (Changala, 2014)

- In Uganda, the CHC project focused on engaging in dialogue with their audiences to determine content and messaging. Instead of the traditional, prescriptive health messages that tell audiences what to do, the project engaged people in a conversation, found out what was important to them and positioned relevant health actions in that context.

- In a project in Liberia, vaccinators asked mothers if they would also like to go for same-day, co-located family planning services to space their children (for rest and health) and mentioned that many other vaccinating mothers were doing it. This addressed the strong social stigma against resuming sex and using family planning before the baby walks (Source: MCHIP Liberia Job Aid for Vaccinators).

- Guidelines from the Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group on freshwater conservation and WASH integration recommended the following widely applicable lesson:

“Resist the urge to design a 50/50 project between WASH and freshwater conservation activities and do not be afraid to rule things out. Projects are context specific. Not all implementation elements can be incorporated for many reasons including lack of financial resources, capacity, community ownership or other constraints. No project can do everything, what matters most is that the project achieves the agreed upon goals.”

- Ghana BCS formed content design teams for each of its health areas (e.g., malaria, family planning, nutrition and WASH). Each team was a small group with representation from approximately five organizations, plus the relevant Ghana Health Service Unit.