About Misoprostol

Uterotonics, including misoprostol, are the most effective medicines to prevent postpartum hemorrhage, which causes one out of every four maternal deaths.

Globally, more than eight million of the 136 million women giving birth each year suffer from excessive bleeding after childbirth. This condition—medically referred to as postpartum hemorrhage (PPH)—causes one out of every four maternal deaths that occur annually and accounts for more maternal deaths than any other individual cause[1]. Deaths due to PPH disproportionately affect women in low-resource countries.

Source: FCI

Commodity Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends using uterotonics such as oxytocin and misoprostol during the third stage of labor to prevent PPH[2]. However randomized controlled trials have shown that misoprostol is less effective than oxytocin and has more side effects, such as high temperature and shivering. As such, oxytocin is the recommended uterotonic for the prevention and treatment of PPH by the WHO. However, in settings where the use of oxytocin, in not possible (due to inadequate training, stock-out, cost, or cold chain issues, for example), WHO recommends 600 micrograms misoprostol orally immediately after the birth of the baby for prevention of PPH or 800 micrograms of misoprostol sublingually as a third line treatment for PPH (WHO, 2009).

Commodity Context

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin—a hormone-like substance—available in an oral tablet form. Uterotonic medicines are needed at every level of the health care system where deliveries occur, from urban hospitals to rural clinics[4]. Since misoprostol is in tablet form, it can be administered by community health workers (CHWs) when skilled birth attendants (SBAs) are not present[3]. If uterotonic medicines, including misoprostol, were available to all women giving birth over a ten year period (2006-2016), it is projected that 41 million postpartum hemorrhage cases could be prevented and 1.4 million lives saved[2]. Excessive bleeding after childbirth can be prevented and significantly reduced with expanded availability of maternal health medicines.

Products Available

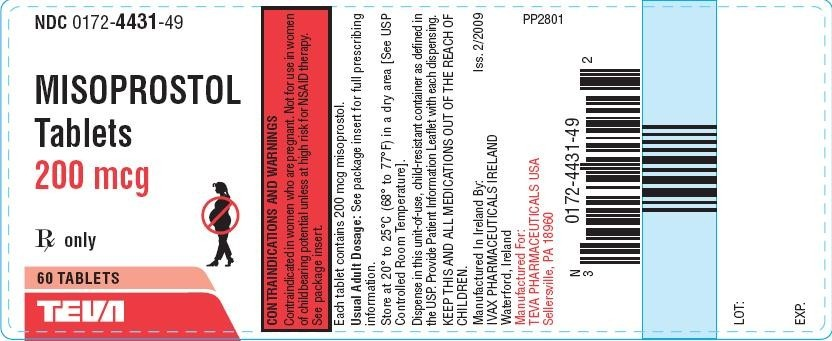

The product is available from more than 50 manufacturers globally (with at least 35 in developing countries) with tablets containing 25, 100, or 200 micrograms of the drug. In some countries, misoprostol is available for purchase in the private market at pharmacies and medicine shops[5]. Tablets of misoprostol can be stored at room temperature but, because they can be affected by moisture, should be appropriately packaged in double-aluminum blister packs. The cost per tablet from manufacturers is approximately US $0.15.

Source: NIH.gov

Product Efficacy

To date, there has not been sufficient evidence from double-blinded randomized control trials to confirm the efficacy of misoprostol. A systematic review by WHO[6] identified and reviewed three studies on efficacy of misoprostol. Two studies in South Africa[7] and Gambia[8] suggested that misoprostol reduced blood loss, but were underpowered to be conclusive about efficacy and safety. The WHO review concluded that more research is needed to confirm its efficacy.

Common Barriers

Misoprostol can also be used to induce labor, prevent and treat gastric ulcers, treat incomplete abortion and miscarriage, and as an abortifacient. The latter use is the main reason some countries are reluctant to recommend it. Misoprostol takes a little longer to work than oxytocin and can have side effects such as chills and fever.

Poor knowledge and attitudes and misperceptions about PPH and misoprostol are important determinants of demand and utilization. Unavailability of the drug, lack of supportive policies, regulatory issues and outdated guidelines also impact demand and uptake, along with reluctance to seek delivery care from skilled health attendants or difficulty in accessing services. However, when misoprostol has been made available in community-based trials, correct usage and perceptions have been overwhelmingly positive.

For more information on misoprostol, please visit the UN Every Woman Every Child initiative webpage.

[1] Children, UN Commission on Life Saving Commodities for Women and. (2012). Comissioner's Report.

[2] Seligman, Barbara; Liu, Xingzhu (2006). Economic Assessment of Interventions for Reducing Postpartum Hemorrhage in Developing countries: Abt Associates Inc.

[3] WHO. (2012). Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage.

[4] JHPIEGO, USAID. (2012). Rapid Landscape Analysis of technologies for postpartum hemorrhage. Conducted by JHPIEGO/Accelovate for USAID at the Technologies for Health Consultative Meeting - MNCH Pathways.

[5] Koski A, Cofi. (2011). Perceptions, use and quality of uterotonic substances in Ghana.

[6] S., Fawcus. (2007). Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage RHL commentary. Geneva: World Health Organization.: The WHO Reproductive Health Library.

[7] Hofmeyr, G Justus, Ferreira, Sandra, Nikodem, V Cheryl, Mangesi, Lindeka, Singata, Mandisa, Jafta, Zukiswa, . . . Gülmezoglu, A Metin. (2004). Misoprostol for treating postpartum haemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN72263357]. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 4(1), 16.

[8] Walraven, Gijs, Dampha, Yusupha, Bittaye, Bubacarr, Sowe, Maimuna, & Hofmeyr, Justus. (2004). Misoprostol in the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage in addition to routine management: a placebo randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 111(9), 1014-1017.